Archives

References

**To unlock access to the first quiz, make sure to select the “Mark as Completed” button below

References

- Smith RC, Verga M, McCarthy S, Rosenfield AT. Diagnosis of acute flank pain: value of unenhanced helical CT. AJR Am J Roentgenol. 1996 Jan;166(1):97–101.

- Miglioretti DL, Johnson E, Williams A, Greenlee RT, Weinmann S, Solberg LI, et al. The use of computed tomography in pediatrics and the associated radiation exposure and estimated cancer risk. JAMA Pediatr. 2013 Aug 1;167(8):700–7.

- Dawn s. Milliner, Mary e. Murphy. Urolithiasis in Pediatric Patients. Mayo Clinic Proceedings, 1993;68(3):241-248, ISSN 0025-6196, https://doi.org/10.1016/S0025-6196(12)60043-3.

- Guedj R, Escoda S, Blakime P, Patteau G, Brunelle F, Cheron G. The accuracy of renal point of care ultrasound to detect hydronephrosis in children with a urinary tract infection. Eur J Emerg Med. 2015 Apr;22(2):135-8. doi: 10.1097/MEJ.0000000000000158. PMID: 24858915.

- Dalziel PJ, Noble VE, Bedside ultrasound and the assessment of renal colic: a review. Emergency Medicine Journal 2013;30:3-8.

- Smith-Bindman R, Aubin C, Bailitz J, Bengiamin RN, Camargo CA, Corbo J, et al. Ultrasonography versus computed tomography for suspected nephrolithiasis. N Engl J Med. 2014 Sep 18;371(12):1100–10.

- Jendeberg J, Geijer H, Alshamari M, Cierzniak B, Lidén M. Size matters: The width and location of a ureteral stone accurately predict the chance of spontaneous passage. Eur Radiol. 2017 Nov;27(11):4775–85.

- Goertz JK, Lotterman S. Can the degree of hydronephrosis on ultrasound predict kidney stone size? Am J Emerg Med. 2010 Sep;28(7):813–6.

- Taus PJ, Manivannan S, Dancel R. Bedside Assessment of the Kidneys and Bladder Using Point of Care Ultrasound. POCUS J. 2022;7(Kidney):94–104.

- Renal Ultrasound Made Easy: Step-By-Step Guide [Internet]. POCUS 101. [cited 2023 Dec 9]. Available from: https://www.pocus101.com/renal-ultrasound-made-easy-step-by-step-guide/

- Ma J, Mateer J. Ma and Mateer’s Emergency Ultrasound. 4e ed. USA: McGraw Hill; 2021.

- The POCUS Atlas. Renal/GU. https://www.thepocusatlas.com/renal-gu.

- Renal Fellow Network [Internet]. 2023 [cited 2023 Dec 10]. Renal Fellow Network. Available from: https://www.renalfellow.org/

- Ripollés T, Martínez-Pérez MJ, Vizuete J, Miralles S, Delgado F, Pastor-Navarro T. Sonographic diagnosis of symptomatic ureteral calculi: usefulness of the twinkling artifact. Abdom Imaging. 2013 Aug;38(4):863–9.

- Kidney. https://nephropocus.com/tag/kidney/.

Summary

Summary

- The urinary tract should be evaluated by visualizing both kidneys and the collecting systems, together with the bladder.

- Each kidney needs to be scanned in the longitudinal and transverse orientation for better identification of abnormalities.

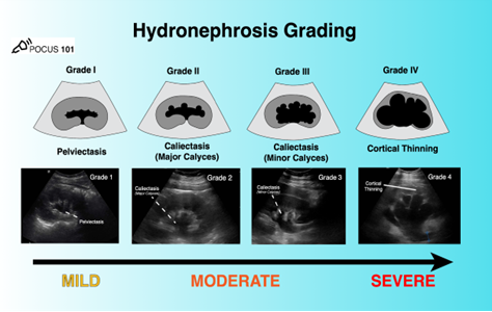

- Hydronephrosis will include multiple grades. It is important to familiarize yourself with the grading system.

- The bladder is an anechoic structure. It should be evaluated in both the transverse and longitudinal orientation.

- Ureteral jets can be viewed with the application of color Doppler in the transverse orientation.

- Be aware of pitfalls when evaluating the renal system and bladder.

Figure 22: Summary of hydronephrosis grading. Image use with permission POCUS 101 [11]

Figure 22: Summary of hydronephrosis grading. Image use with permission POCUS 101 [11]

Pitfalls

Pitfalls

As with all PoCUS imaging, care must be taken to understand the limitations of imaging the kidney and collecting duct system. First, care must be taken to avoid incorrectly ascribing hydronephrosis due to obstruction in a patient with a full bladder or one who is over hydrated. Ideally patients undergoing evaluation of the urinary tract should be well hydrated, but not overly so, and have a partly filled, but not distended bladder. Care must also be taken not to mistake prominent hypoechoic renal pyramids in pediatric patients for hydronephrosis. Their location is outside the renal sinus in contrast to hydronephrosis, which always occurs inside the renal sinus.

In addition, PoCUS imaging is limited for direct visualization of suspected renal calculi. Nephrolithiasis is possible even if the stone cannot be visualized. Lastly, the absence of hydronephrosis does not rule out a renal stone as small stones may not cause hydronephrosis. If hydronephrosis is detected on PoCUS, further evaluation with a formal ultrasound by radiology, and potentially a KUB X-ray, is recommended to assess for the presence and size of renal stones.

Lastly, there are several normal or pathological findings that can be misinterpreted as hydronephrosis on ultrasound. Careful technique and interpretation are essential to avoid false positives. These include:

- Extrarenal Pelvis: a normal and often benign anatomical variant that lies predominantly outside the renal sinus. An extrarenal pelvis on ultrasound will appear as an anechoic structure adjacent to the renal sinus without any pelviectesis, caliectasis, or cortical thinning. You can also place color doppler over it to make sure there is no arterial or venous flow present. (Figure 18)

- Parapelvic Cysts: non-malignant, fluid-filled anechoic structures formed near the renal pelvis and therefore can be mistaken for hydronephrosis. The anechoic areas of cysts are localized and do not connect to the calyces. They are round or oval making them distinguishable from hydronephrosis. Any findings of suspected renal cysts should be followed up with a formal renal ultrasound. (Figure 19)

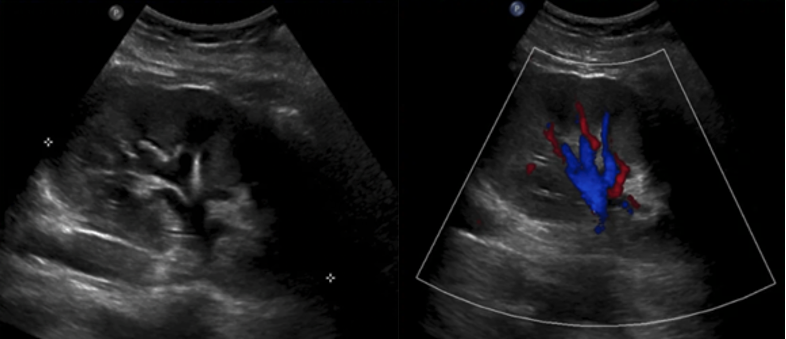

- Prominent renal arteries/veins and Renal Vascular Malformations can also cause false positives for hydronephrosis. Color Doppler indicates blood flow and can distinguish renal prominent vessels or vascular malformations from hydronephrosis.(Figure 20)

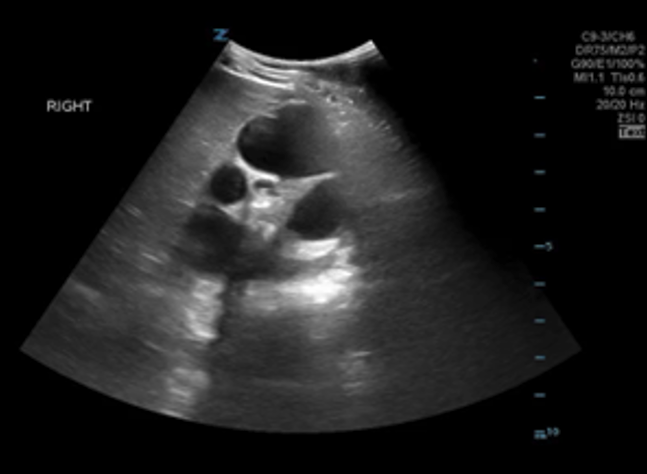

- Polycystic Kidney Disease (PCKD) and Acquired Renal Cystic Disease (ARCD) are diseases in which there will be an abundance of irregular renal cysts of varying size that distort the kidney’s shape bilaterally and can sometimes be mistaken for severe hydronephrosis. (Figure 21)

Figure 18: Short axis of the right kidney with an extra renal pelvis. [12]

Figure 18: Short axis of the right kidney with an extra renal pelvis. [12]

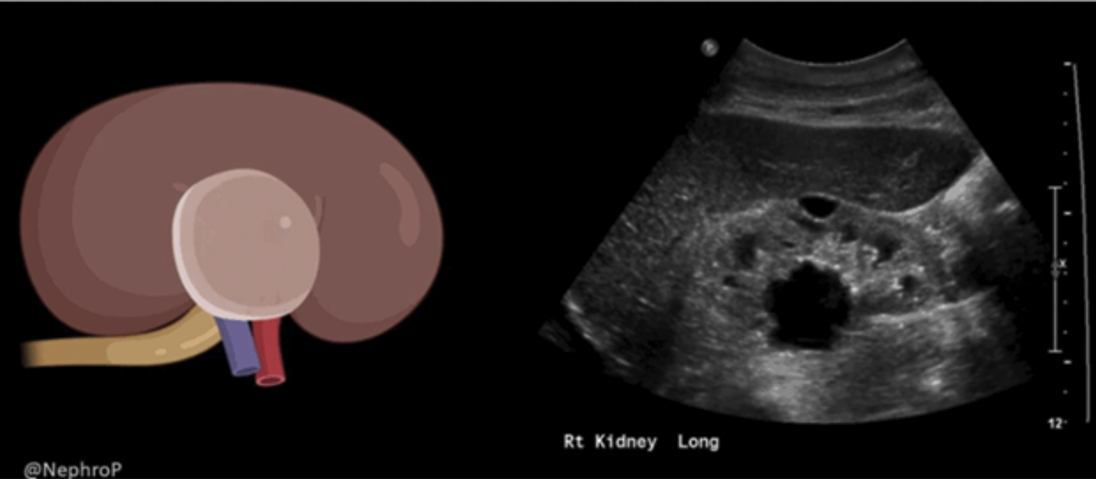

Figure 19: Sagittal image of the right kidney with a parapelvic cyst. Image use with permission from Nephro POCUS [15]

Figure 19: Sagittal image of the right kidney with a parapelvic cyst. Image use with permission from Nephro POCUS [15]

Figure 20: Sagittal 2D and color image of the kidney with prominent vasculature at the renal pelvis. Image use with permission from Nephro POCUS [15]

Figure 20: Sagittal 2D and color image of the kidney with prominent vasculature at the renal pelvis. Image use with permission from Nephro POCUS [15]

Figure 21: Sagittal image of a kidney with PCKD

Figure 21: Sagittal image of a kidney with PCKD

What is NOT Normal

Hydronephrosis

Hydronephrosis is defined as an abnormal enlargement and distension of a kidney caused by obstructive uropathy (blockage of normal urine flow into the bladder). Patients may present with varying symptoms depending on the causes of hydronephrosis [10]. On ultrasound, this appears as abnormal distension of the renal pelvis which is normally not visible within the fat of the renal sinus. Depending on the degree of obstruction, hydronephrosis can be graded according to severity.

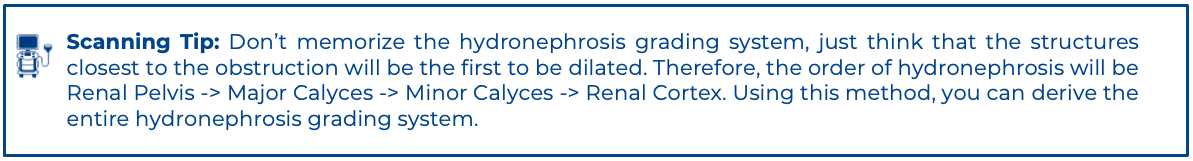

Grade 1 Hydronephrosis or “Mild” Hydronephrosis

Occurs when there is dilatation of the renal pelvis (pelviectasis) without dilatation of the calyces. The renal cortex (parenchyma) is preserved and does not show any atrophy.

Figure 11: Longitudinal ultrasound image of the kidney with corresponding anatomical diagram, demonstrating pelviectasis. Image use with permission POCUS 101 [10].

Figure 11: Longitudinal ultrasound image of the kidney with corresponding anatomical diagram, demonstrating pelviectasis. Image use with permission POCUS 101 [10].

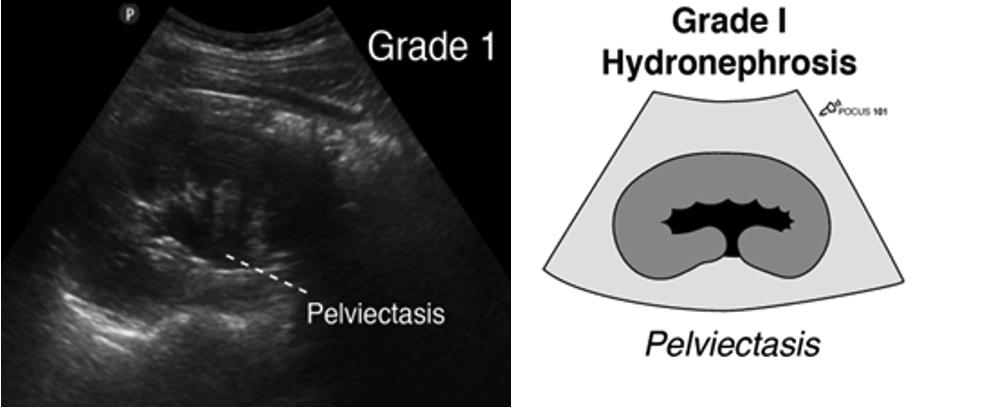

Grade 2 Hydronephrosis (Mild-Moderate)

Occurs when you have dilatation of the renal pelvis (pelviectasis) and dilatation of the calyces (caliectasis), specifically the MAJOR calyces. The renal cortex (parenchyma) is preserved and does not show any atrophy.

Figure 12: Longitudinal ultrasound image of the kidney with matching anatomical illustration, showing pelviectasis and dilation of the major calyces. Image use with permission POCUS 101 [10].

Figure 12: Longitudinal ultrasound image of the kidney with matching anatomical illustration, showing pelviectasis and dilation of the major calyces. Image use with permission POCUS 101 [10].

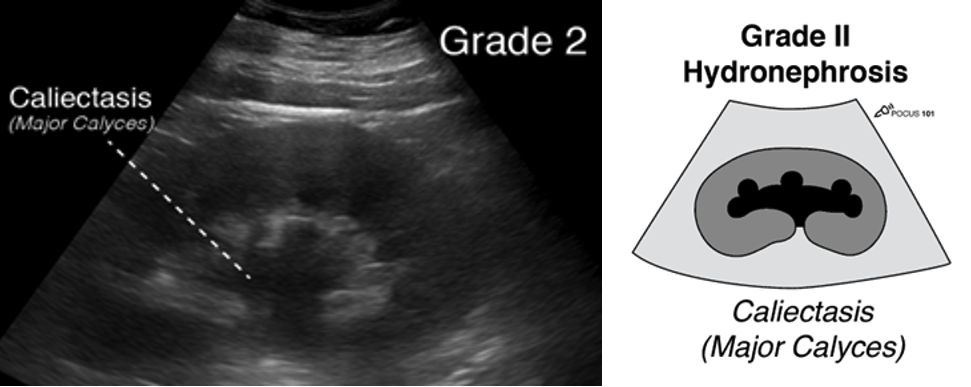

Grade 3 Hydronephrosis or “Moderate” Hydronephrosis

Occurs when you have dilatation of the renal pelvis (pelviectasis) and dilatation of the calcyces (caliectasis), specifically the major and minor Mild cortical thinning may be seen.

Figure 13: Longitudinal ultrasound image of the kidney with matching anatomical illustration, showing pelviectasis and dilation of the major and minor calyces. Image use with permission POCUS 101 [10].

Figure 13: Longitudinal ultrasound image of the kidney with matching anatomical illustration, showing pelviectasis and dilation of the major and minor calyces. Image use with permission POCUS 101 [10].

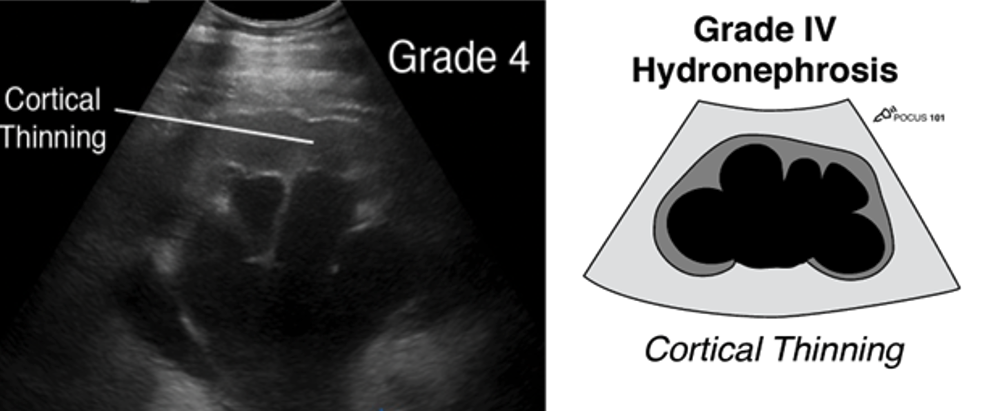

Grade 4 Hydronephrosis or “Severe” Hydronephrosis

Occurs when there is significant/gross dilatation of the renal pelvis (pelviectasis) and calcyces (caliectasis) resulting in renal cortical thinning. There will also be renal atrophy and loss of the borders between the renal pelvis and calyces.

· Grade 4 hydronephrosis is also sometimes called the “Bear Claw” sign since the anechoic areas resemble a paw print.

Figure 14: Longitudinal ultrasound image of the kidney with matching anatomical illustration, showing pelviectasis, caliectasis and cortical thinning. Image use with permission POCUS 101 [10]

Figure 14: Longitudinal ultrasound image of the kidney with matching anatomical illustration, showing pelviectasis, caliectasis and cortical thinning. Image use with permission POCUS 101 [10]

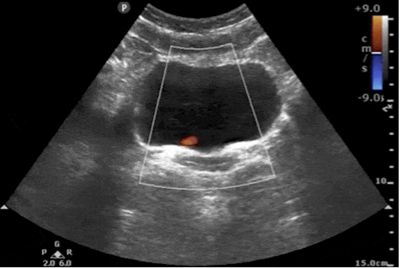

Absence of Ureteral Jets

In cases of obstructive uropathy, either from stones or other causes, absence of ureteric jets in addition to hydronephrosis can be appreciated in the bladder indicating a blockage urine passing from the kidney to the bladder. Absence of jets is highly suspicious for obstructive uropathy and formal imaging follow up with radiological US or CT scan is recommended.

Figure 15: Transverse bladder with absent left uretic jet

Figure 15: Transverse bladder with absent left uretic jet

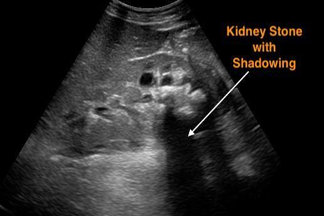

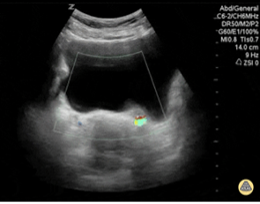

Ultrasound Findings for Kidney Stones

PoCUS for the direct visualization of kidney stones is limited. Formal radiology has high sensitivity and specificity for identification of stones depending on the experience of the institution but is generally not reliable at the bedside. Sometimes renal stones can be seen in the renal cortex, pelvis, or the ureteropelvic junction appearing as a hyperechoic structure with posterior shadowing.

The “twinkling artifact” is a sonographic artifact located behind calcifications of ureteral calculi when color Doppler is applied. It will appear as a multicolored high-intensity signal, like signals produced by turbulent flow with aliasing. The twinkling artifact has a sensitivity and specificity of 90% and 100%, respectively, for kidney stone at the ureterovesical junction [14]. The twinkling artifact should not be confused with ureteric jets, which are found within the fluid of the bladder, not behind the posterior wall.

Figure 16: Sagittal image of the right kidney with a large stone displaying posterior enhancement in the lower pole. Image use with permission POCUS 101 [10].

Figure 16: Sagittal image of the right kidney with a large stone displaying posterior enhancement in the lower pole. Image use with permission POCUS 101 [10].

Figure 17: Transverse color image of the bladder showing twinkle artefact at the left UVJ indicative of a stone. Image use with permission from POCUS Atlas [12]

Figure 17: Transverse color image of the bladder showing twinkle artefact at the left UVJ indicative of a stone. Image use with permission from POCUS Atlas [12]

What is Normal

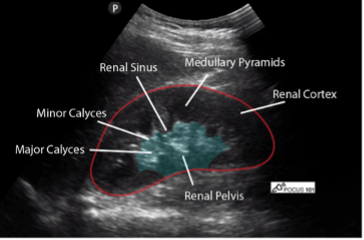

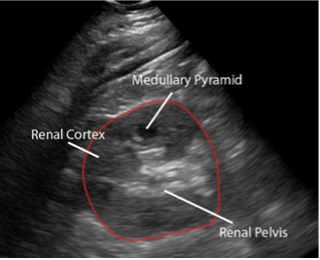

The echogenic capsule makes the bean-shaped organ easily identifiable. The cortex is either isoechoic or hypoechoic (more commonly) compared with the normal liver or normal spleen. However, in neonates and young infants, the renal cortex may appear more echogenic than the liver, which is a normal age-related finding. The renal cortical tissue extends into the medulla, separating the pyramids in the form of columns called columns of Bertin. The medullary pyramids are hypoechoic or anechoic compared to the cortex. On most occasions, the pyramidal shape is not well visualized but is often better seen in small children. Renal sinus fat is echogenic and occupies a major part of the inner kidney. The collecting system is usually not visualized unless distended and is embedded in the surrounding echogenic sinus fat. The renal pelvis area is hypoechoic but not “black” unless there is hydronephrosis. Similarly, ureters are not typically seen unless distended as in hydroureter [13].

Figure 9: Normal right kidney in longitudinal view with labeled renal anatomy. Image use with permission POCUS 101 [10]

Figure 10: Normal left kidney in longitudinal view with labeled renal anatomy Image use with permission POCUS 101 [10]

Bladder

Renal ultrasound should always include a bladder assessment (covered in the prerequisite KidSONO Bladder Volume Module). However, In the context of hydronephrosis, additional imaging of the bladder with color Doppler is needed to assess for ureteric jets, as their presence or absence may indicate ureteric obstruction.

*For details on bladder scanning technique and protocol, please refer to the prerequisite KidSONO Bladder Volume module prior to continuing with this module.

Normal Ureteric jets

Urine flows from the kidney, through the ureters, and finally enters the bladder at the trigone. Ultrasound “Ureteral Jets” are a color Doppler finding during bladder ultrasound that detects the flow of urine into the bladder at the level of the trigone. As urine flows into a filled bladder, the ureteral jets appear as color signals that flow in an anteromedial direction and should cross the midline [11].

Assessing for Ureteric Jets:

- In the transverse plane, apply color or power doppler along the posterior wall of the bladder around the trigone

- Use a low flow scale 10-20cm/s with doppler box placed over the posterior wall.

- Of note, urine is not continuously released into the bladder so you may need to wait up to 5-10 minutes to see if there are any ureteral jets in the bladder.

Figure 8: Transverse bladder with power doppler displaying normal ureteric jets. Image use with permission from the Pocus Atlas [12]

Left Kidney

Left Kidney

Technique

The technique for scanning the left kidney is very similar to that of the right kidney. Of note, the left kidney lies slightly superior, and posterior compared to the right kidney due to the smaller size of the spleen.

- Identify the kidney in the longitudinal view:

· Place the probe along the left posterior axillary line around the level of the xiphoid with the probe indicator directed towards the patient’s head

· Slide the probe until the spleen comes into view: the left kidney is located more superior, and posterior compared to the right kidney. To view the left kidney, the scanner’s knuckles are often touching the bed in the posterior axillary line

· Once the spleen is visualized slide, fan and heel the probe to identify the left kidney and center it on the screen

· Adjust depth and gain if necessary and magnify the kidney to optimize the image

- Assess the LK in transverse view:

· From sagittal, rotate the probe 90 degrees counterclockwise so the probe marker is oriented anteriorly

· Slide or fan the probe from cranial to caudal to assess the kidney in its entire transverse view

Figure 5: Patient/probe position for sagittal assessment of the left kidney

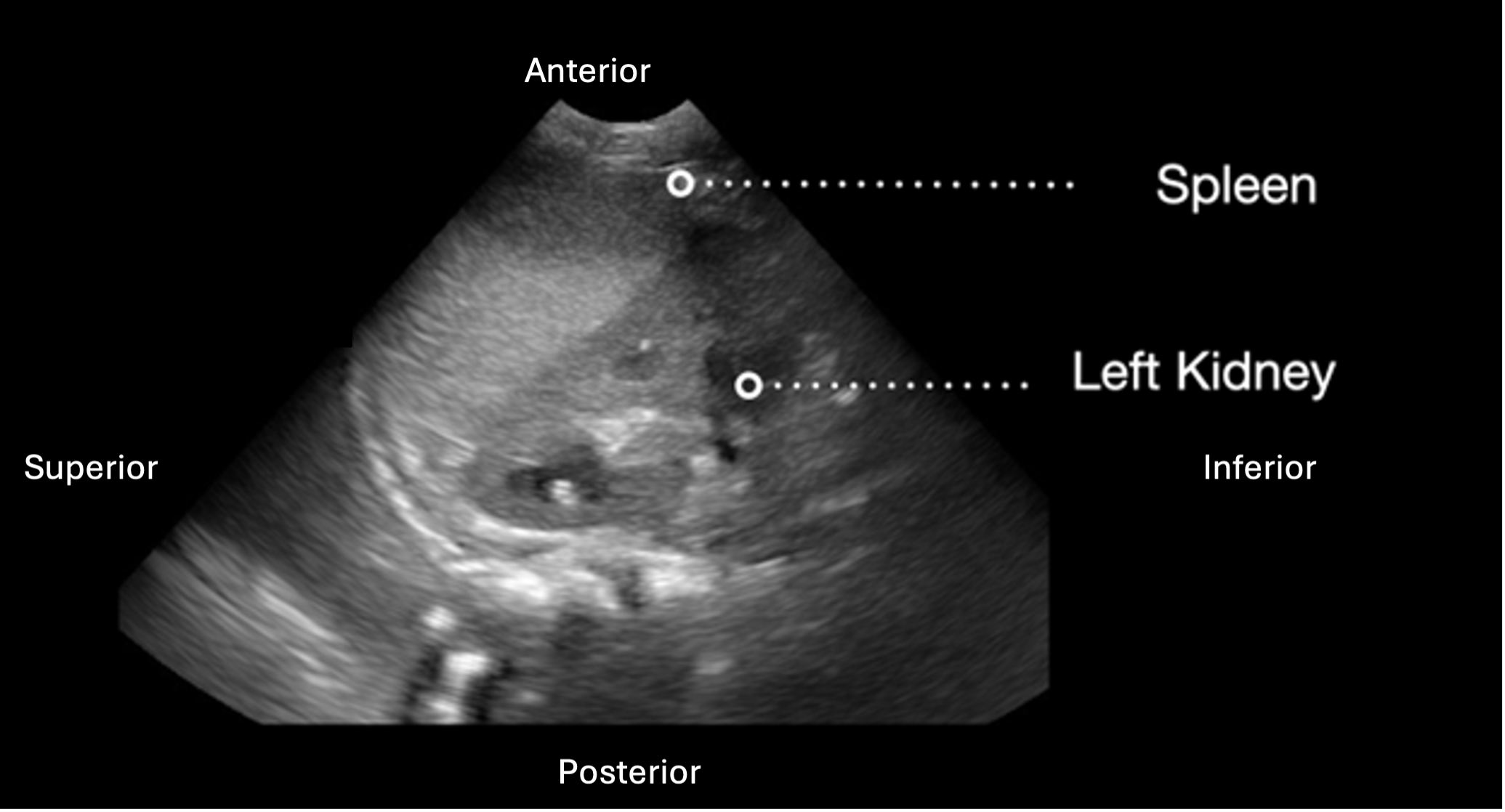

What am I Looking at?

The left kidney is located just inferior and slightly medial to the spleen. The spleen appears homogeneously echogenic with a uniform texture and is less vascular than the liver. On ultrasound, the spleen is typically slightly more echogenic than the left kidney.

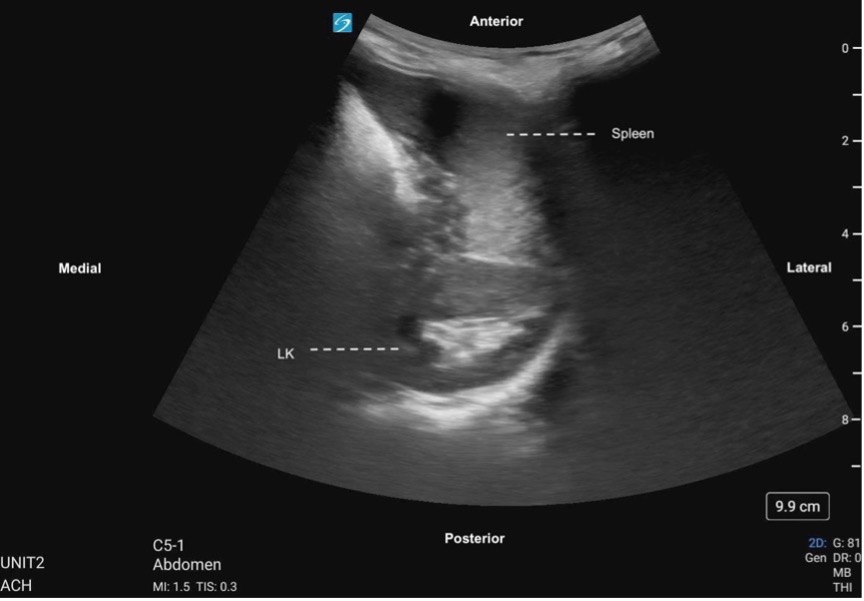

Figure 6: Longitudinal view of the left kidney with labeled image orientation and surrounding structures

Figure 6: Longitudinal view of the left kidney with labeled image orientation and surrounding structures

Figure 7. Left kidney transverse, labeled with image orientation and surrounding structures

Figure 7. Left kidney transverse, labeled with image orientation and surrounding structures

Figure 8: Transverse sweep of the LK

Right Kidney

Right Kidney

Technique

- Identify the kidney in the longitudinal view:

· Place the probe in the right midaxillary line at the level of the xyphoid process with the probe indicator towards the patient’s head.

· Slide the probe posteriorly and anteriorly until the kidney is located

· Adjust the view by sliding the probe to ensure the kidney is centered in the field of view.

· Adjust depth and gain if necessary and magnify the kidney to optimize the image.

- Assess the RK in transverse view:

· From sagittal, rotate the probe 90 degrees counterclockwise so the probe marker is oriented posteriorly

· Slide or fan the probe from cranial to caudal to assess the kidney in its entire transverse view

Figure 1. Patient and probe position for right kidney assessment. Image use with permission POCUS 101 [10].

What am I Looking at?

The right kidney is located just inferior and slightly lateral to the liver. The liver appears homogeneously echogenic with a smooth, uniform texture and contains prominent vascular structures. The right kidney is slightly less echogenic than the liver

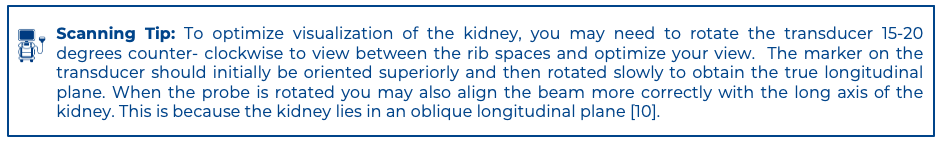

Figure 2. Longitudinal view of the right kidney with labeled image orientation and surrounding structures

Figure 2. Longitudinal view of the right kidney with labeled image orientation and surrounding structures

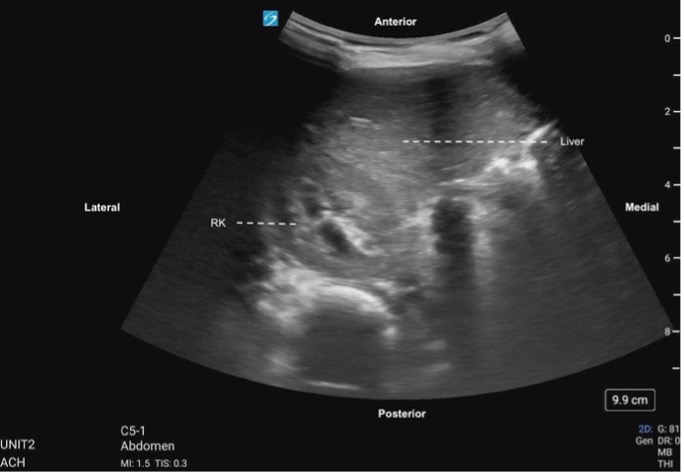

Figure 3. Right kidney transverse, labeled with image orientation and surrounding structures

Figure 3. Right kidney transverse, labeled with image orientation and surrounding structures

Figure 4: Right kidney transverse

Technique Overview

Machine prep:

- Image the patient in B-mode

- Choose an abdominal or renal pre-set

- Enter patient and practitioner ID for archiving as per local policy

Patient Preparation

The patient should be laid supine

TIP: in the case of difficult views, the patient can be sat up, laid in the decubitus position or prone

TIP: Raise the ipsilateral arm above the head to spread the rib spaces allowing probe placement posterolaterally.

TIP: If cooperation is an issue, particularly in young children, the patient can be seated or lying in a parent’s lap to help keep them calm and still during the scan

Scanning Technique Overview

1. Longitudinal/sagittal kidney assessment

2. Transverse kidney assessment

3. Repeat sagittal and transverse assessment on opposite kidney

4. Sagittal and Transverse assessment of the bladder

5. Color doppler of the bladder to assess for Jets

For bilateral kidney assessment, be sure to:

· Identify and assess the renal structures: the cortex, medulla pyramids and renal pelvis

· Consider imaging any abnormalities with color doppler as well to differentiate vascular from other structural abnormalities

· Save stills and clips in the mid longitudinal and transverse views as per local policy