Several pathologic findings can disrupt normal patterns in the eye as seen on ultrasound. The following conditions represent important pediatric ocular pathologies that can be identified with ultrasound and should be recognized as abnormal.

Abnormalities of the lens

Abnormalities of the lens are observed either by changes in its position within the eye (dislocation) or by alterations in its contour or echogenicity (cataracts).

Lens Dislocation

Lens dislocation is the displacement of the lens from its normal position. It can be acquired (often traumatic) or congenital (ectopia lentis).

· Sonographic appearance: The normally circular, echogenic lens is displaced from its central location behind the iris, floating or tilted in the posterior chamber or vitreous. “Floating lens sign” refers to when the lens is seen moving freely with eye movements.

Figure 8. Lens dislocation evidenced by the displacement of the lens in the vitreous at the posterior aspect of the globe. Video courtesy of Dr. Jade Seguin, used with permission.

Contour & Echogenicity

Any variation from the normal smooth, anechoic lens can indicate an abnormality of the lens.

· Sonographic appearance: If the lens appears heterogeneous, thickened, irregular in contour, or hyperechoic, this suggests a structural or developmental abnormality, such as congenital or acquired cataracts.

Figure 9. Abnormal lens evidenced by its irregular contour with a thickened, hyperechoic appearance. Findings were ultimately consistent with cataracts. Video courtesy of Dr. Jade Seguin, used with permission.

Abnormalities of the Vitreous

Vitreous Hemorrhage

Vitreous Hemorrhage refers to bleeding into the vitreous chamber of the eye. In children, it can be caused by various intraocular diseases, however, is most commonly caused by trauma [20].

· Sonographic appearance: The appearance will vary depending on the amount of blood. It may appear as echogenic debris within the vitreous chamber, or a hyperechoic focus/membrane deep in the vitreous.

Figure 10. Vitreous hemorrhage as seen by the echogenic debris within the vitreous. Video courtesy of Dr. Jade Seguin, used with permission.

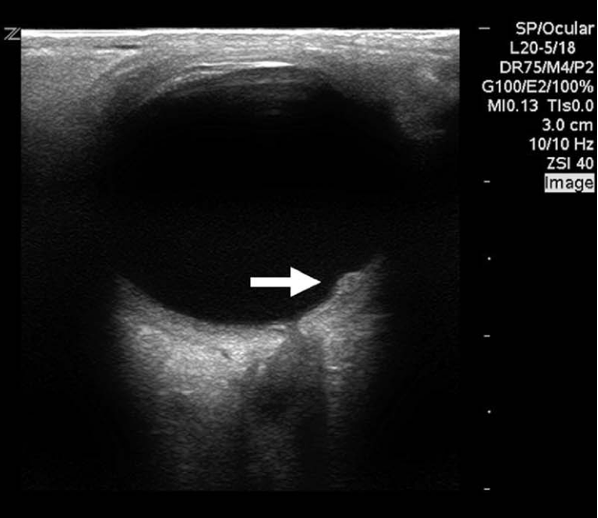

Vitreous Detachment

Vitreous detachment is usually benign and does not lead to vision loss. It refers to the separation of the posterior vitreous body from the retina. It is uncommon in children and usually occurs secondary to trauma.

Sonographic appearance:

· A Hyperechoic membrane will be seen floating in the vitreous. The membrane will NOT be tethered to the optic disc, but rather it will be free floating in the posterior chamber.

· Vitreous hemorrhages remain horizontal when the patient moves their eye side to side.

· Most often seen in the middle section of the posterior eye

Figure 11. Vitreous detachment. Note how there is no connection to the optic nerve and the horizontal appearance of the detachment membrane. Video courtesy of Dr. Eric Roseman, Kings County Emergency Medicine, via POCUS Atlas . Used under CC BY-NC 4.0 license.

Abnormalities of the Retina

Any disruption of the normally thin, echogenic, and anchored retinal layer can indicate a pathology.

Retinal Detachment

Retinal detachments can lead to permanent vision loss if not treated in a timely manner. Retinal detachment occurs when the sensory layer of the retina separates from the underlying retinal pigment epithelium. In children, trauma is the most common cause, although other congenital or acquired conditions can also lead to detachment [20].

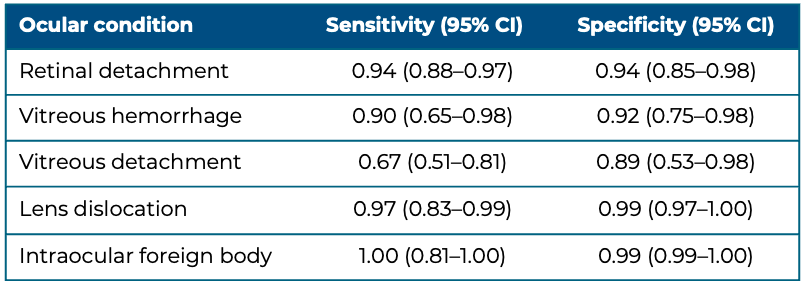

Sonographic appearance:

· A thin, hyperechoic membrane will be seen floating in the vitreous. The membrane will be tethered posteriorly at the optic nerve head. This gives a “V-shaped” appearance.

· A detached retina will move with eye motion but remain anchored posteriorly at the ON head.

** This anchoring will distinguish retinal detachment from a vitreous hemorrhage and detachment**

· Small detachments will be tethered closed to the posterior aspect of the eye and will move less with eye movements [21].

Figure 12. Retinal Detachment, with a “V-shaped” appearance due to anchoring to the ON head. Image courtesy of Dr. Michael Kidon, Denver Health Emergency Medicine, via POCUS Atlas . Used under CC BY-NC 4.0 license.

Figure 12. Retinal Detachment, with a “V-shaped” appearance due to anchoring to the ON head. Image courtesy of Dr. Michael Kidon, Denver Health Emergency Medicine, via POCUS Atlas . Used under CC BY-NC 4.0 license.

Masses and structural changes

Any thickening or focal lesion arising from or within the retina should be considered abnormal. This may represent tumors (e.g. retinoblastoma), bleeding (retinal hemorrhages), vascular anomalies (e.g. Coat’s disease), or developmental structural changes.

· Sonographic appearance: Thickening or echogenic structures within or extending from the retinal layer, distinct from the thin, normally smooth retina. Echogenicity may be variable, and calcifications may be present (e.g. retinoblastoma).

Figure 13. Posterolateral mass protruding from the retina in a child with Coats disease. Image courtesy of Dr. Jade Seguin, used with permission.

Figure 13. Posterolateral mass protruding from the retina in a child with Coats disease. Image courtesy of Dr. Jade Seguin, used with permission.

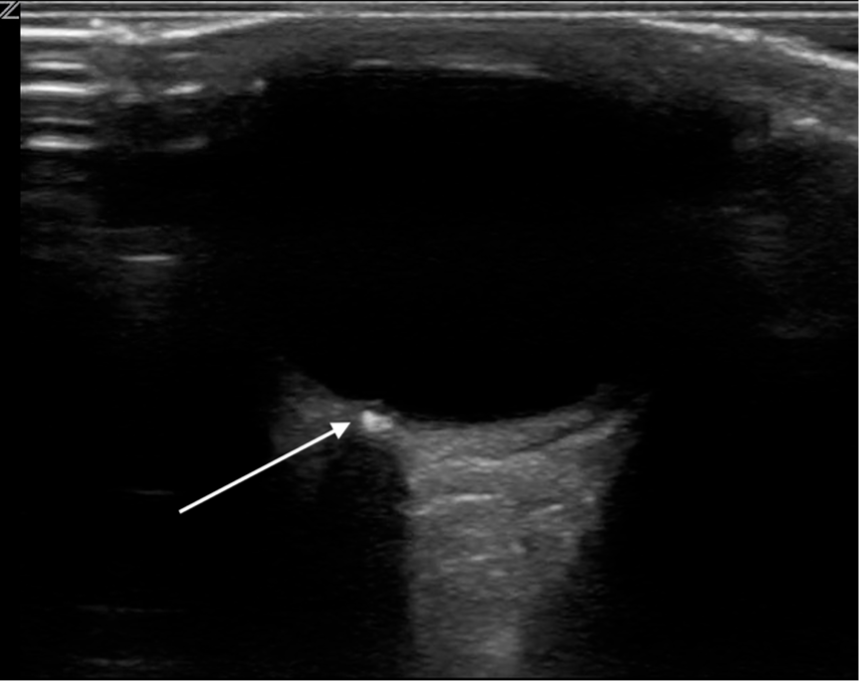

Intraocular Foreign Bodies (IOFB)

Foreign materials (metal, glass, wood, etc.) can become lodged in the globe of the eye and can often be visualized with ultrasound.

Key Considerations: IOFB may be associated with vitreous hemorrhage, retinal detachment and/or globe rupture.

If an IOFB is visualized, stop scanning immediately and notify ophthalmology. This helps prevent further displacement of the foreign body and protects against worsening injury if the globe is ruptured, since any pressure could precipitate complications or extrusion of intraocular contents.

· Sonographic appearance: Foreign material will appear as a hyperechoic object with posterior acoustic shadowing, reverberation or comet tail artifact [20]. IOFB can be located in the anterior chamber, lens, vitreous, retina, or other regions of the globe, depending on the mechanism and trajectory of injury.

Figure 14. Hyperechoic structure seen anteriorly, adjacent to the globe. Note that with dynamic eye movements the foreign body does not move suggesting this is outside of the globe. Video courtesy of Dr. Robert Jones, MetroHealth Medical Center / Case Western Reserve University, via POCUS Atlas . Used under CC BY-NC 4.0 license.

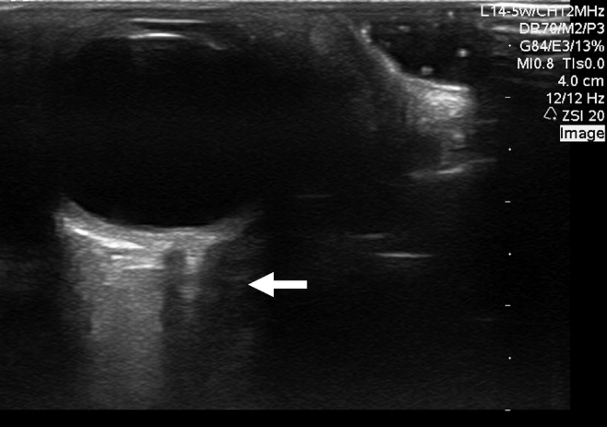

Periorbital Abnormalities

Abnormalities of the periorbital tissues can be identified by changes in tissue echogenicity, swelling, or the presence of fluid collections. Assess for hypoechoic or anechoic areas, asymmetry between orbits, restricted extraocular eye movement, and disruption of normal soft tissue planes. Examples include:

Soft tissue edema/cellulitis: Diffuse hypoechoic thickening of the periorbital soft tissues. Often poorly defined and may involve the eyelids and surrounding orbital tissues

Abscess: Well-defined, localized hypoechoic or anechoic collection with irregular borders; may show internal echoes and sometimes posterior enhancement.

Glioma: A mass arising from the optic nerve or adjacent to the orbit, which may cause displacement of ocular tissue

Orbital Fractures: PoCUS can he used to assess for fractures of the infraorbital rim and lateral orbital wall [22-25]. Fractures will be seen as a discontinuity or displacement of the echogenic bone cortex [25].

Figure 15. Hypoechoic collection in the medial retro-orbital fat of the right orbit. Subsequent CT confirmed a right medial orbital abscess. Image courtesy of Dr. Jade Seguin, used with permission.

Figure 15. Hypoechoic collection in the medial retro-orbital fat of the right orbit. Subsequent CT confirmed a right medial orbital abscess. Image courtesy of Dr. Jade Seguin, used with permission.

Optic Disk Variants and Findings

Both anatomical variants and optic disc pathologies may occasionally be observed during ocular ultrasound. While these are discussed in greater detail in the KidSONO Optic Nerve Module, it is useful to recognize how they may appear in relation to the posterior globe and retinal plane:

Optic Disc Drusen (figure 16): Drusen are acellular deposits that calcify over time. They are typically buried in early childhood, becoming superficial around age 12 [27]. In early childhood, the buried deposits push the optic nerve head anteriorly into the vitreous, appearing as focal elevations of the optic disk from the posterior globe. Late in childhood they can appear as echogenic foci (due to calcified deposits) with posterior shadowing located at the optic disk. They are typically bilateral.

Tilted Optic Discs (figure 17): Represent an anatomical variant in which the optic disc is oriented obliquely. This results in an apparent elevation or irregular contour of the posterior globe that can mimic pathology, buts its simply due to the disc’s oblique angle.

Figure 16. Optic disk drusen. Image courtesy of Dr. Jade Seguin, used with permission

Figure 17. Video demonstrating a tilted optic disc, which can be seen at the posterior globe/retinal plane. Video courtesy of Dr. Jade Seguin, used with permission

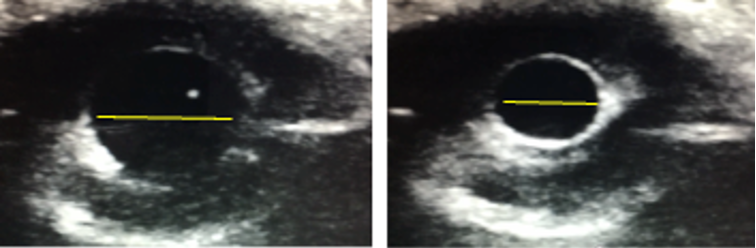

Pupillary Response

PoCUS can be used as an adjunct to assess pupillary response through closed eyelids using standardized light stimulation. It can be particularly valuable in pediatric trauma and critically ill children where direct assessment may be limited. Ultrasound assessment has shown excellent agreement with clinical examination for pupillary light reflex, including direct and consensual responses (ICC 0.93–0.96; agreement 87.36%) [28].

The transducer is placed transversely on the lower eyelid at approximately a 45-degree angle from the globe, using a torchlight for pupillary light reflex examination [28].

Sonographic findings suggestive of abnormal pupillary response include:

· Absent or reduced pupillary constriction

· Delayed or asymmetric response,

· Absent consensual response

Figure 18. Ocular PoCUS assessment of pupillary response through closed eyelids. B-mode images demonstrate pupillary diameter measurement at baseline (left) and following light stimulation (right). Image courtesy of Dr. Jade Seguin, used with permission

Globe Rupture

In suspected globe rupture, POCUS is contraindicated because even minimal probe pressure can cause extrusion of intraocular contents and worsen structural damage. Clinical features that raise concern include a peaked or irregular pupil, markedly decreased visual acuity, a shallow anterior chamber, hyphema, or obvious laceration. In this setting PoCUS should NOT be performed. Avoid any pressure on the eye: place a rigid eye shield, keep the patient NPO, provide analgesia and antiemetics to prevent Valsalva, and obtain urgent ophthalmology consultation.

In the case that globe rupture was not the clinical suspicion, and PoCUS was performed, it will appear as:

· Loss of normal spherical shape of the globe

· Flattening of the anterior chamber

· Buckling of the sclera

· Vitreous hemorrhage

Figure 19. POCUS of the right orbit following blunt ocular demonstrating complete loss of normal globe architecture, consistent with globe rupture. Video courtesy of Dr. Earl Cummings, MUSC Emergency and Pediatric Emergency Medicine, via POCUS Atlas . Used under CC BY-NC 4.0 license.

Figure 5. Normal ocular ultrasound of the right eye, labeled.

Figure 5. Normal ocular ultrasound of the right eye, labeled. Figure 6. Normal eye on PoCUS.

Figure 6. Normal eye on PoCUS.

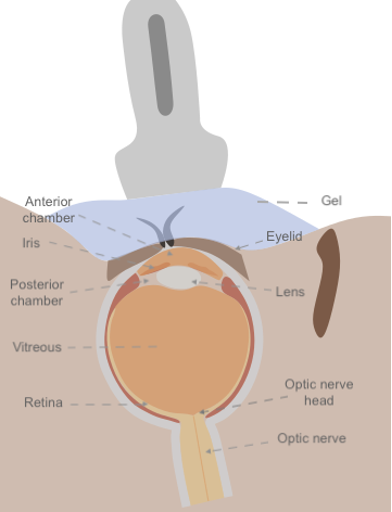

Figure 4: Anatomical diagram of the eye in relation to ocular ultrasound

Figure 4: Anatomical diagram of the eye in relation to ocular ultrasound

Figure 2. Transverse probe position during ocular PoCUS with Tegaderm and copious gel

Figure 2. Transverse probe position during ocular PoCUS with Tegaderm and copious gel Figure 3. Sagittal probe position during ocular PoCUS with Tegaderm and copious gel

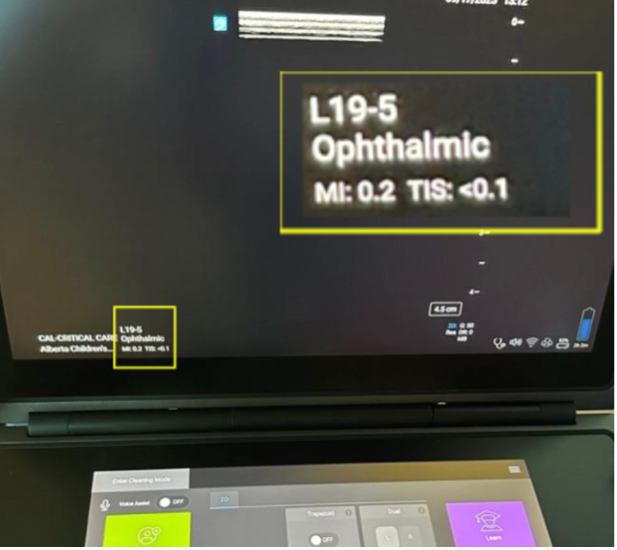

Figure 3. Sagittal probe position during ocular PoCUS with Tegaderm and copious gel Figure 1. Acceptable MI and TI as seen on ophthalmic preset of a Sonosite PoCUS unit.

Figure 1. Acceptable MI and TI as seen on ophthalmic preset of a Sonosite PoCUS unit.