What is NOT normal?

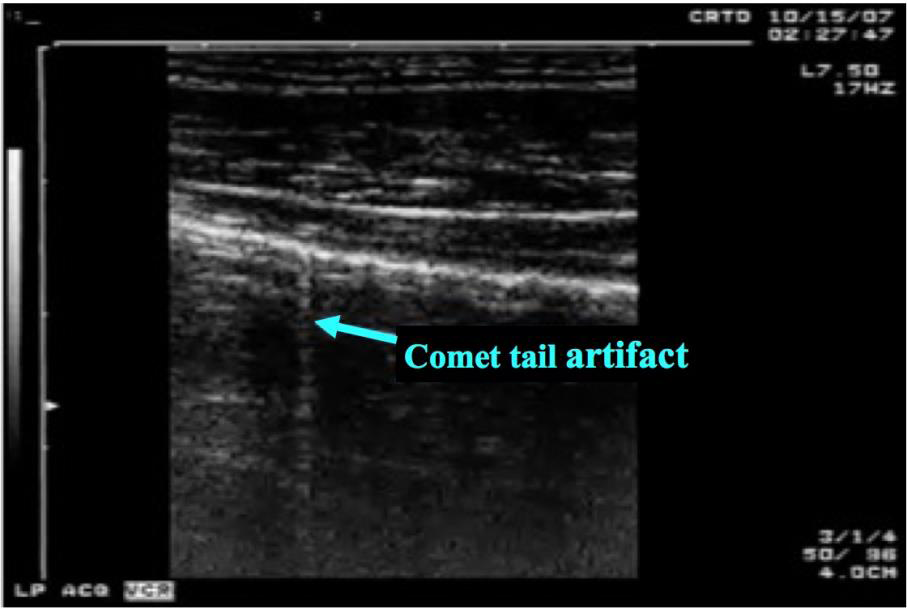

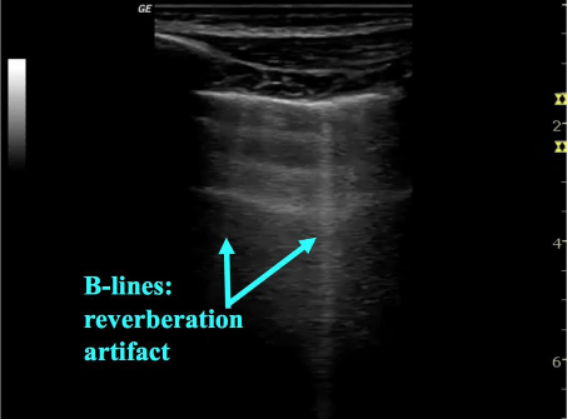

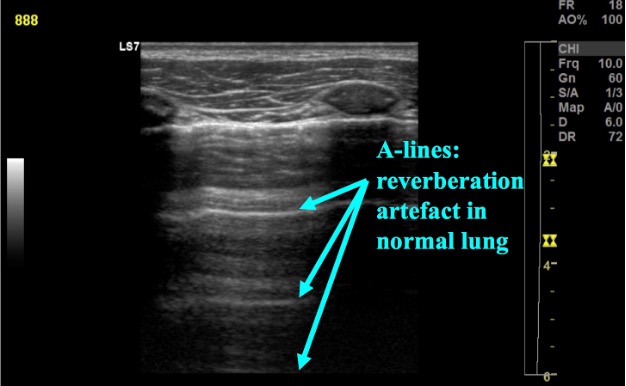

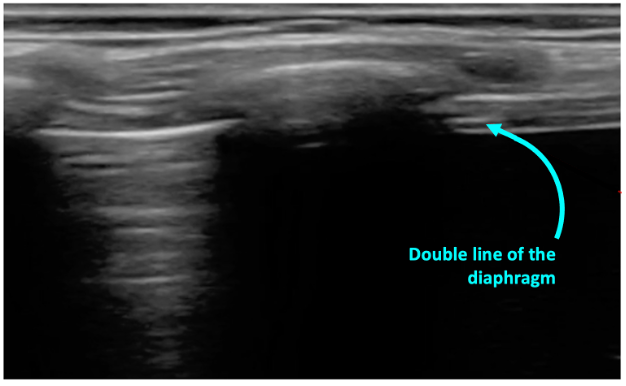

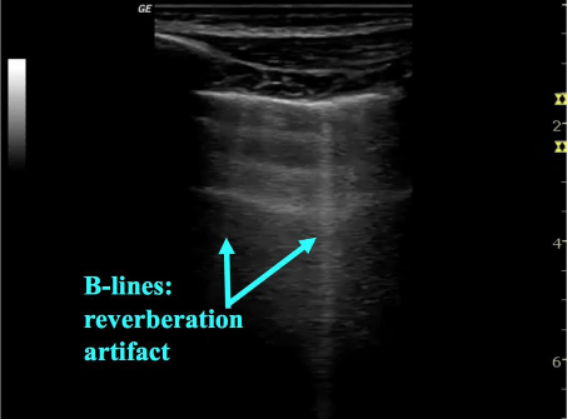

Interstitial syndromes of the lung include a variety of pathologic conditions that involve either localized or diffuse involvement of the lung. The thickened interlobular septa from fibrosis, edema or excess extravascular lung water result in a characteristic appearance on ultrasound. In these conditions the air-filled alveoli and water-filled interstitium interact to create a reverberation artifact called B-lines. B-lines are characterized as (figure 4):

- Sharp, vertical lines

- Arising from the pleura and extending to the edge of the screen

- Move with respiration

- Erase A-lines

Figure 4: Sonographic B-line

While one or two B-lines can sometimes be seen normally in dependent portions of lung or areas of interlobar fissures, when more than three are seen in one field of view they are considered pathological. In addition, when B-lines are seen diffusely in the chest in multiple fields of view, particularly in non-dependent areas they indicate pathology.

Quantifying B-lines

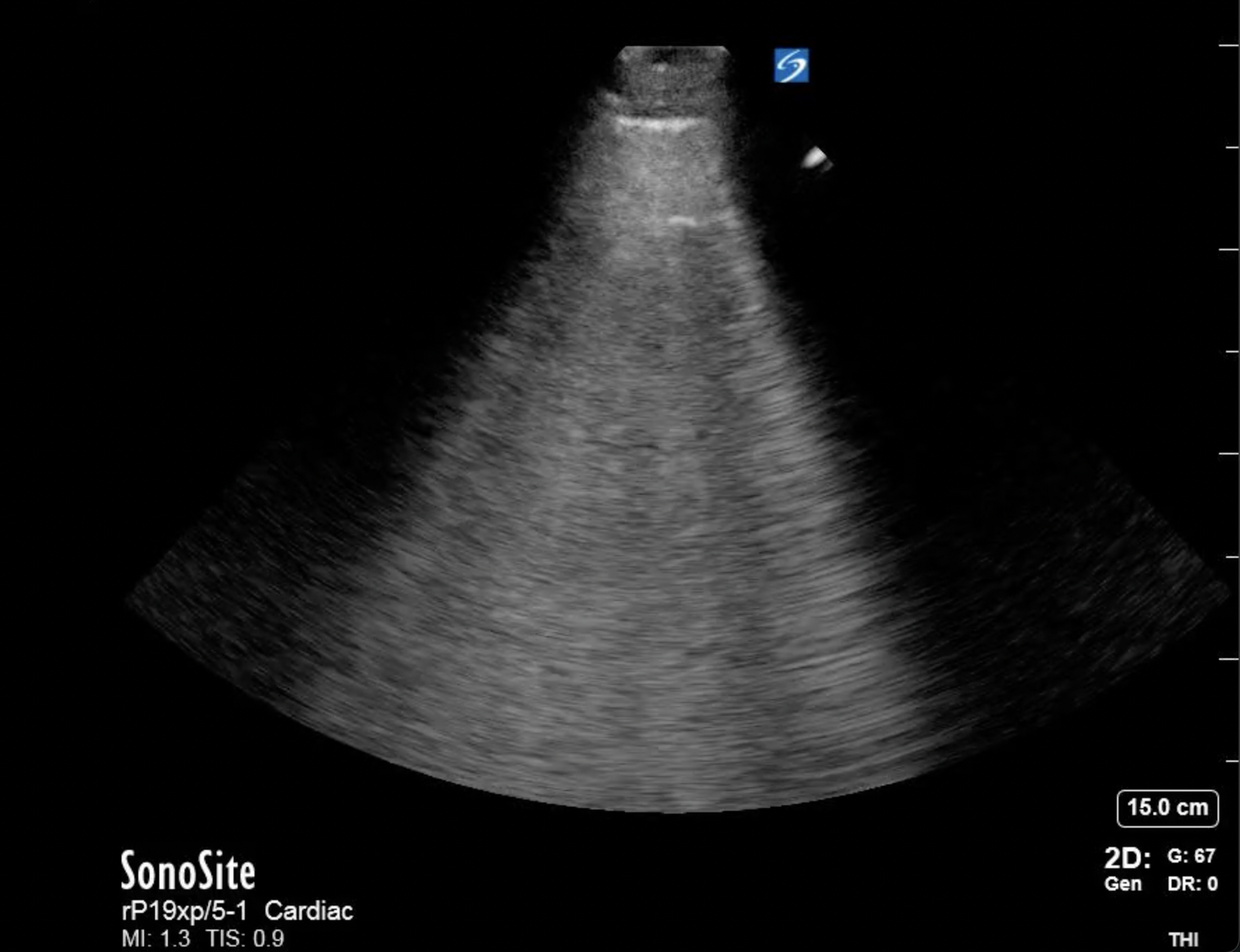

In the acute setting, a qualitative assessment of LUS findings is usually adequate. The number of B-lines on ultrasound correlates well with disease severity as well as response to therapy. In less severe diseases B-lines appear multiple and discrete, as disease progresses, they can become confluent giving a “white out appearance of the lung (figure 5). Studies have shown that B-lines rapidly resolve in response to treatment for heart failure and through the course of dialysis for those with ESRD [11]. In addition, B-lines and other abnormalities found in patients with viral pneumonia, ARDS and bronchiolitis resolve along with their clinical course [1,3].

Figure 5: In severe disease B-lines coalesce and form confluent B-lines resulting in a “white out” appearance of the lung.

In non-critical patients a more careful assessment with quantification of B-lines can be useful for assessment and monitoring response to therapy. While beyond the scope of this module there are several techniques described to quantify B-lines.

Interpreting B-lines

Sonographic B lines have multiple causes including pulmonary edema, infection, ARDS, contusion, and fibrosis; US interpretation must occur within the clinical context. Focal B-lines with associated pleural line abnormalities or consolidation indicate pneumonia or contusion (video 2).

Video 2: Focal B-lines adjected to pleural irregularity with consolidation in bacterial pneumonia

Multifocal but patchy B-lines with spared areas can be seen in bronchiolitis, viral pneumonia, pneumonitis, contusion, ARDS and fibrosis—often along with pleural line abnormalities and/or small subpleural consolidations. Finally diffuse and homogenous B-lines with a regular pleural line is a pattern expected pulmonary edema or fluid overload (video 3) [2]. Generally, the patient’s history and clinical information can help guide the diagnosis improving the sensitivity and specificity of LUS in diagnosing specific etiologies.

Video 3: Diffuse and symmetric B-lines with a normal pleural line in a patient with congestive heart failure.