Archives

Introduction

KidSONO: Left Ventricular Function

Author: Julia Stiz, MSc, RDCS

Secondary Author: Melanie Willimann, MD, FRCPC

Reviewer(s): Jackie Harrison, M.D., FRCPC; Mark Bromley, M.D., FRCPC; Nicholas Packer, M.D., FRCPC; Kim Myers, M.D., FRCPC

*To continue through to the course, make sure to select the “Mark as Completed” button below.

References

**To unlock access to the first quiz, make sure to select the “Mark as Completed” button below

References

- Patel, G et al. Point-of-Care Cardiac Ultrasound (POCCUS) in the Pediatric Emergency Department. Clinical Pediatric Emergency Medicine. 2018. 19: 323-327. DOI: 10.1016/j.cpem.2018.12.009

- Guevarra K, Greenstein Y. Ultrasonography in the Critical Care Unit. Curr Cardiol Rep. 2020;22(11):145. doi:10.1007/s11886-020-01393-z

- Volpicelli G, Lamorte A, Tullio M, et al. Point-of-care multiorgan ultrasonography for the evaluation of undifferentiated hypotension in the emergency department. Intensive Care Med. 2013;39(7):1290-1298. doi:10.1007/s00134-013-2919-7

- Potter SK, Griksaitis MJ. The role of point-of-care ultrasound in pediatric acute respiratory distress syndrome: emerging evidence for its use. Ann Transl Med. 2019;7(19):507-507. doi:10.21037/atm.2019.07.76

- Mojoli F, Bouhemad B, Mongodi S, Lichtenstein D. Lung Ultrasound for Critically Ill Patients. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2019;199(6):701-714. doi:10.1164/rccm.201802-0236CI

- Daley JI, Dwyer KH, Grunwald Z, et al. Increased Sensitivity of Focused Cardiac Ultrasound for Pulmonary Embolism in Emergency Department Patients With Abnormal Vital Signs. Runyon MS, ed. Academic Emergency Medicine. 2019;26(11):1211-1220. doi:10.1111/acem.13774

- Taylor RA, Moore CL. Accuracy of emergency physician-performed limited echocardiography for right ventricular strain. The American Journal of Emergency Medicine. 2014;32(4):371-374. doi:1016/j.ajem.2013.12.043

- Popat A, Yadav S, Pethe G, Rehman A, Sharma P, Rezkalla S. The role of POCUS in diagnosing acute heart failure in the emergency department: A meta-analysis. Journal of Cardiology. Published online June 2025. doi:1016/j.jjcc.2025.06.012

- Dresden S, Mitchell P, Rahimi L, et al. Right Ventricular Dilatation on Bedside Echocardiography Performed by Emergency Physicians Aids in the Diagnosis of Pulmonary Embolism. Annals of Emergency Medicine. 2014;63(1):16-24. doi:1016/j.annemergmed.2013.08.016

- Chico S, Connolly S, Hossain J, Levenbrown Y. Accuracy of Point‐Of‐Care Cardiac Ultrasound Performed on Patients Admitted to a Pediatric Intensive Care Unit in Shock. J of Clinical Ultrasound. 2025;53(3):445-451. doi:1002/jcu.23883

- Griffee MJ, Merkel MJ, Wei KS. The role of echocardiography in hemodynamic assessment of septic shock. Crit Care Clin. 2010;26(2):365-382, table of contents. doi:10.1016/j.ccc.2010.01.001

- Watkins LA, Dial SP, Koenig SJ, Kurepa DN, Mayo PH. The Utility of Point-of-Care Ultrasound in the Pediatric Intensive Care Unit. J Intensive Care Med. Published online October 9, 2021:088506662110478. doi:10.1177/08850666211047824

- Gaspar HA, Morhy SS. The Role of Focused Echocardiography in Pediatric Intensive Care: A Critical Appraisal. BioMed Research International. 2015;2015:1-7. doi:10.1155/2015/596451 de Boode WP, van der Lee R, et al. The role of Neonatologist Performed Echocardiography in the assessment and management of neonatal shock. Pediatr Res. 2018;84(S1):57-67. doi:10.1038/s41390-018-0081-1

- Arnoldi S, Glau CL, Walker SB, et al. Integrating Focused Cardiac Ultrasound Into Pediatric Septic Shock Assessment*. Pediatric Critical Care Medicine. 2021;22(3):262-274. doi:10.1097/PCC.0000000000002658

- Ranjit S, Aram G, Kissoon N, et al. Multimodal Monitoring for Hemodynamic Categorization and Management of Pediatric Septic Shock: A Pilot Observational Study*. Pediatric Critical Care Medicine. 2014;15(1):e17-e26. doi:10.1097/PCC.0b013e3182a5589c

- Singh Y, Tissot C, Fraga MV, et al. International evidence-based guidelines on Point of Care Ultrasound (POCUS) for critically ill neonates and children issued by the POCUS Working Group of the European Society of Paediatric and Neonatal Intensive Care (ESPNIC). Crit Care. 2020;24(1):65. doi:10.1186/s13054-020-2787-9

- Lu JC, Riley A, Conlon T, et al. Recommendations for Cardiac Point-of-Care Ultrasound in Children: A Report from the American Society of Echocardiography. Journal of the American Society of Echocardiography. 2023;36(3):265-277. doi:1016/j.echo.2022.11.010 1.

- Sanz J, Sánchez-Quintana D, Bossone E, Bogaard HJ, Naeije R. Anatomy, Function, and Dysfunction of the Right Ventricle. Journal of the American College of Cardiology. 2019;73(12):1463-1482. doi:1016/j.jacc.2018.12.076

- Kaul S, Tei C, Hopkins JM, Shah PM. Assessment of right ventricular function using two-dimensional echocardiography. American Heart Journal. 1984;107(3):526-531. doi:1016/0002-8703(84)90095-4

- Sato T, Tsujino I, Oyama-Manabe N, et al. Simple prediction of right ventricular ejection fraction using tricuspid annular plane systolic excursion in pulmonary hypertension. Int J Cardiovasc Imaging. 2013;29(8):1799-1805. doi:1007/s10554-013-0286-7 1.

- Nickson C. The Dark Art of IVC Ultrasound. Life in the Fast Lane. Published November 3, 2020. Accessed October 22, 2025. https://litfl.com/the-dark-art-of-ivc-ultrasound/

- EL-Nawawy AA, Omar OM, Hassouna HM. Role of Inferior Vena Cava Parameters as Predictors of Fluid Responsiveness in Pediatric Septic Shock: A Prospective Study. Journal of Child Science. 2021;11(01):e49-e54. doi:1055/s-0041-1724034 1.

- De Souza TH, Giatti MP, Nogueira RJN, Pereira RM, Soub ACS, Brandão MB. Inferior Vena Cava Ultrasound in Children: Comparing Two Common Assessment Methods*. Pediatric Critical Care Medicine. 2020;21(4):e186-e191. doi:1097/PCC.0000000000002240

- POCUS 101. The D Sign – Right Heart Strain from Pressure vs Volume Overload. POCUS 101. Published August 7, 2017. Accessed August 18, 2025. https://www.pocus101.com/the-d-sign-right-heart-strain-from-pressure-vs-volume-overload/

- Mah K, Mertens L. Echocardiographic Assessment of Right Ventricular Function in Paediatric Heart Disease: A Practical Clinical Approach. CJC Pediatric and Congenital Heart Disease. 2022;1(3):136-157. doi:1016/j.cjcpc.2022.05.002

- Conlon TW, Baker D, Bhombal S. Cardiac point-of-care ultrasound: Practical integration in the pediatric and neonatal intensive care settings. Eur J Pediatr. 2024;183(4):1525-1541. doi:1007/s00431-023-05409-y

Summary

- POCUS is a rapid and focused tool for assessing RV strain, offering more timely insights than the physical exam alone and providing useful preliminary information to guide further cardiology evaluation and management.

- POCUS should be used as a rule-in tool, not a rule-out test, especially when clinical suspicion for RV strain is high. A normal or unclear POCUS exam does not exclude pathology and should not replace formal imaging when concern persists

- Always assess for RV strain from the standard windows (PLAX, PSAX, A4C, and subxiphoid 4-chamber/IVC) to ensure consistency and accuracy.

- On ultrasound, RV strain is characterized by RV dilation, septal flattening (from pressure or volume overload), and, in more advanced cases, reduced systolic function and IVC plethora.

- Be mindful of the limitations, both technical (e.g., foreshortening, off-axis views, poor acoustic windows) and interpretive (e.g., variability in qualitative assessment).

Pitfalls and Limitations

As with all pediatric cardiac PoCUS, obtaining adequate imaging windows remains a central challenge in the assessment of RV strain. Visualizing the RV can be additionally challenging due to anatomical considerations such as cross-sectional variability and the more horizontal cardiac axis often seen in infants and young children [10]. Lung interference is also common, as right heart structures are frequently obscured by overlying lung tissue. In addition, child cooperation is a recurring obstacle in pediatric imaging; the use of caregivers and distraction techniques is often necessary to improve success.

Similar to LV function assessment, RV strain imaging is susceptible to foreshortening and off-axis imaging. In the PSAX window, a low imaging window or off-axis rotation can produce apparent septal flattening (“pseudoflattening”) (figure 24, 25), which may mimic RVVO and/or RVPO and lead to inappropriate conclusions or interventions [17, 24,25]. In the A4C view, foreshortening may occur when imaging from too high of an intercostal space, making the RV appear truncated or blunted (figure 26,27). Always confirm you are at the appropriate intercostal space by scanning through adjacent levels in each window.

Similarly, IVC interpretation carries technical limitations. In children receiving positive pressure ventilation, the IVC shows reversed respiratory variation, and its craniocaudal and mediolateral motion during respiration can introduce apparent changes in caliber, potentially leading to overestimation of collapsibility or distensibility [22,23]. In addition, only the extremes (marked collapse or minimal/no collapse) are truly informative in pediatric 2D IVC assessment; intermediate appearances are unreliable and should be interpreted cautiously within the overall clinical context [21].

Because of these technical challenges, some studies have shown that in pediatric RV strain PoCUS examinations, fewer than half of the obtained images are adequate for qualitative assessment [10]. Even in light of these limitations, supplemental qualitative measures are still not recommended for pediatric RV strain PoCUS at this time due to the difficulty in defining normal values for pediatric populations [26]. Quantitative assessment should be saved for formal echocardiography, where time permits access to normal values charts relative to age and body surface area.

In practice, qualitative interpretation often relies on comparing RV size and function to that of the LV. However, this relative approach carries pitfalls: if the LV is dilated or dysfunctional, the RV may appear deceptively normal by comparison, when it may also be abnormal (figure 28). It is therefore important to always consider global cardiac function when interpreting RV findings.

Lastly, differentiation of RVVO and RVPO septal flattening can be difficult, particularly in PoCUS settings without ECG gating. Any flattening of the IVS should prompt formal echocardiography for further evaluation [17]. Formal echocardiography should also be pursued when image quality is suboptimal, interpretation is uncertain, or there are clinical concerns for RV strain, even if PoCUS findings appear normal [17].

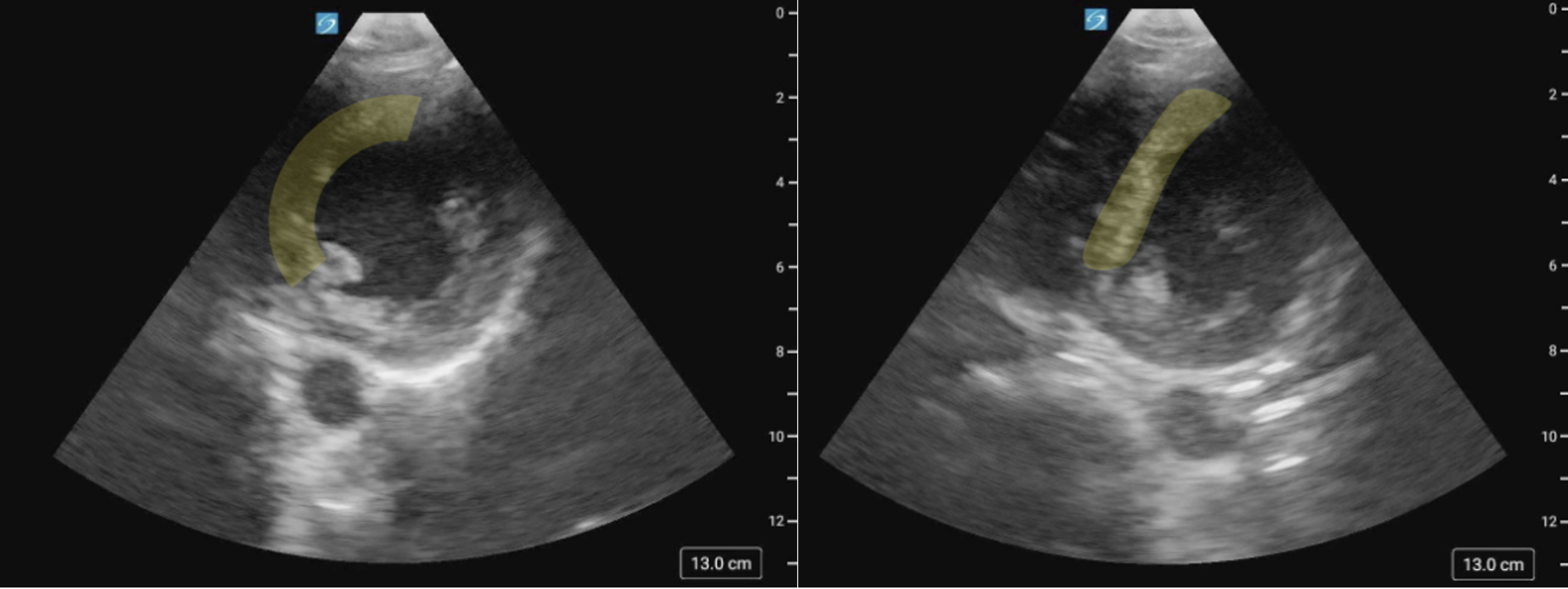

Figure 24 (a) PSAX image of the IVS on axis versus (b) Pseudoflattening of the IVS in the same patient, secondary to a low scanning window.

Figure 25 (a) PSAX view of the IVS on axis versus (b) Pseudoflattening of the IVS in the same patient, secondary to a low scanning window.

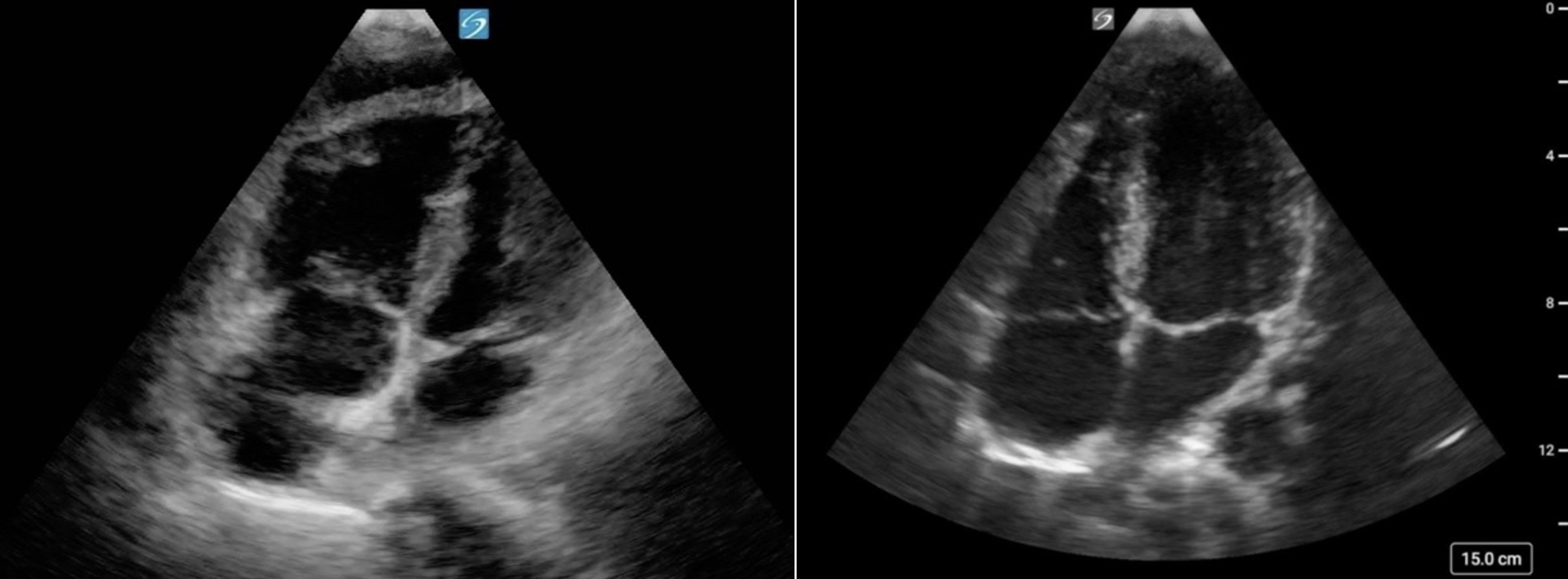

Figure 26. Foreshortened RV in the A4C view

Figure 27. (a) Foreshortened RV in the A4C view. Note the blunted RV apex and loss of the triangular apical tip compared to (b) Elongated RV with triangular tip in the A4C view

Figure 28: A4C cardiology convention, showing RV dilation alongside LV dilation. Although the RV appears smaller than the LV, it is also enlarged.

Subxiphoid IVC

Subxiphoid IVC

The subxiphoid view visualizes the IVC as it enters the right atrium. The IVC appears as an anechoic, tubular, collapsible structure. Visually assessing the size and respiratory variation of the IVC may help estimate right atrial pressure and volume status, though this is not well correlated [21].

IVC diameter cutoff values are established for adults, however no such reference standards exist for the pediatric population. Some evidence supports the use of IVC-to-aortic ratios; however, these are unreliable and limited in practice. Therefore, a qualitative assessment focusing on IVC collapsibility and distensibility is recommended for pediatric RV strain assessment. And while the presence of collapsibility is reassuring, only the extremes (marked collapse or minimal/no collapse) are truly informative in 2D assessment of the pediatric population.

Assessment should be made in the long axis with the IVC displayed horizontally.

What is Normal?

- Small caliber

- Highly collapsible

** In children receiving positive pressure ventilation (PPV), the IVC behaves differently than in spontaneous breathing: its diameter expands during inspiration and contracts during expiration [22]. It is important to consider this when assessing the IVC in children receiving PPV.

Figure 20: Subxiphoid IVC view in cardiology convention demonstrating normal diameter and respiratory variation.

What is NOT Normal?

- A plethoric IVC with little to no respiration

· In these cases, it is important to question why the IVC appears distended with minimal variation (e.g., RV strain, tamponade).

- Flat/nearly collapsed

· May suggest hypovolemia or distributive states; fluid administration might be warranted, but always interpret in the context of the overall clinical picture.

Practice Pearl:

Intermediate appearances, where the IVC is neither flat, highly collapsable or plethoric, are unreliable and challenging to interpret in pediatric populations. The extremes (marked collapse or minimal/no collapse) are the findings that are informative. Always prioritize the clinical context over IVC PoCUS findings alone.

Figure 21: Subxiphoid IVC view cardiology convention demonstrating plethoric IVC with little to no collapse with respiratory variation.

M-Mode of the IVC

Mmode can be applied to the IVC to help visualize and quantify respiratory variation.

> The standard assessment point is just caudal to the hepatic vein confluence [23].

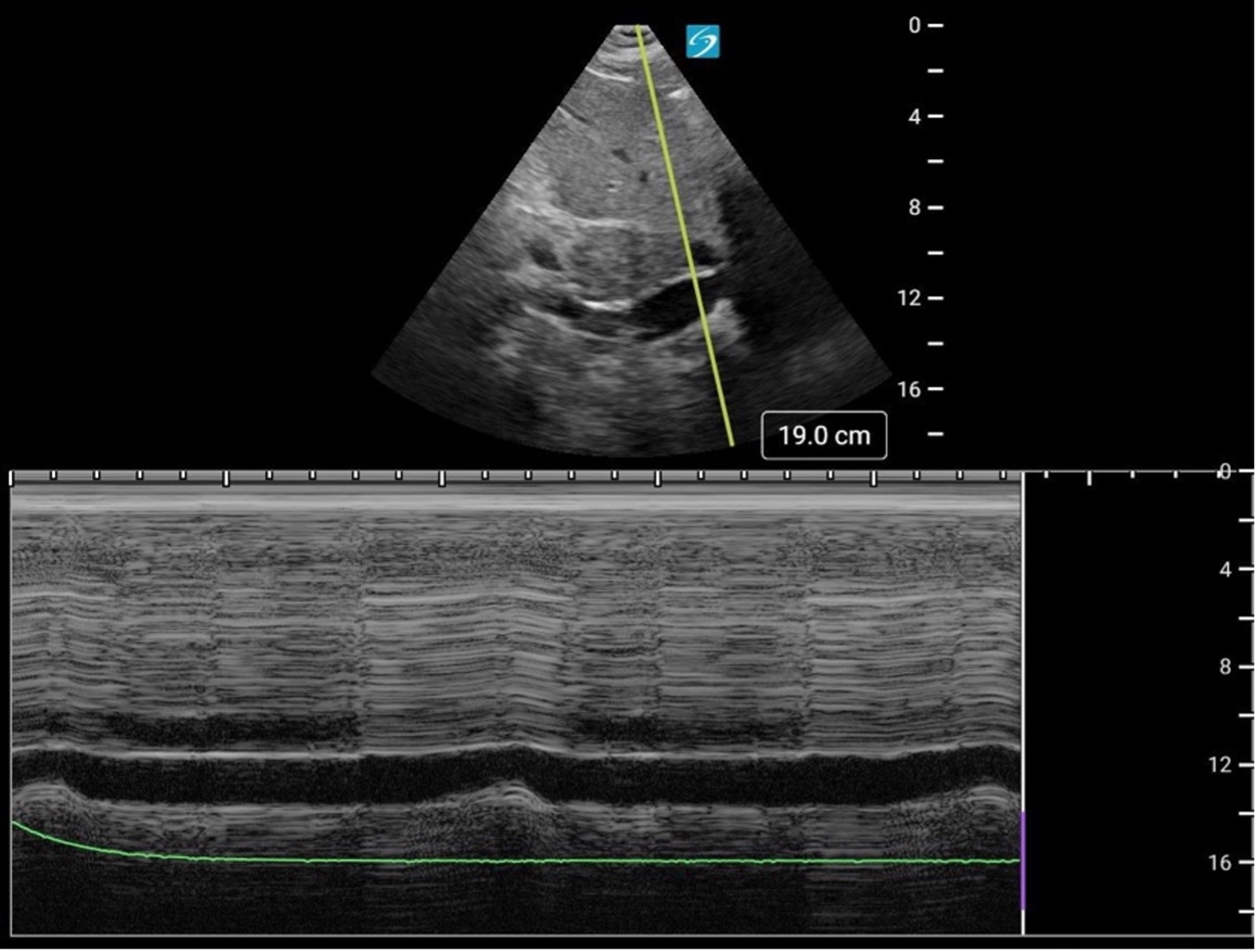

> On M-mode, the IVC will appear as a thin, anechoic band which will change in diameter over the respiratory cycle, creating a wavelike pattern that reflects the vessel’s dynamic collapse and distension (figure 22).

A key limitation to be aware of on assessment of the IVC is that the IVC moves in both craniocaudal and mediolateral directions during respiration. These movements can introduce error as this displacement cannot always be detected in longitudinal 2D or Mmode. This can potentially lead to underestimating IVC caliber and overestimation of collapsibility and distensibility (figure 23) [23].

Figure 22. Mmode of the IVC from the subxiphoid position.

Figure 23. Subxiphoid Mmode of the IVC demonstrating lateral displacement, falsely suggesting IVC collapse.

Advanced Practice Pearl: Color Doppler of the Hepatic veins

Hepatic vein Doppler assessment on PoCUS can provide indirect evidence of RV strain. This represents an advanced PoCUS skill and will be covered in a future KidSONO advanced practice module.

Subxiphoid Four Chamber

The subxiphoid 4 chamber view is particularly well suited for RV assessment due to the anterior position of the RV and the ability to use the liver as an acoustic window. This view provides excellent visualization of the RV free wall and is especially useful for evaluating RV free wall motion, wall thickness, RV size and global function.

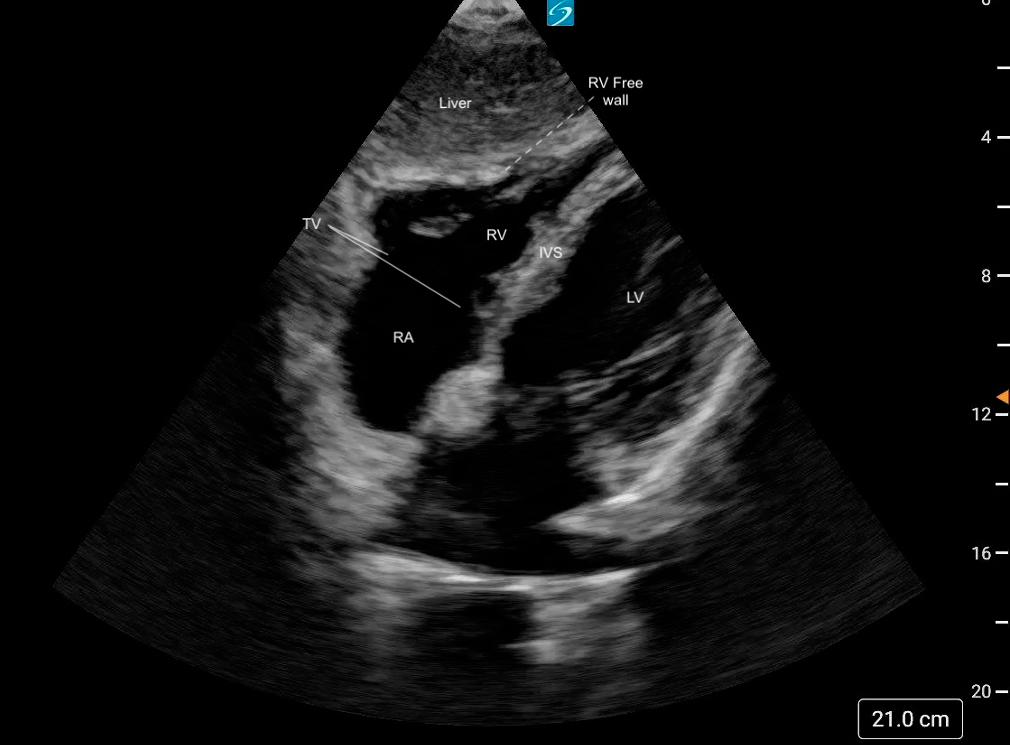

Figure 17. Normal subxiphoid 4 chamber view labeled

Figure 17. Normal subxiphoid 4 chamber view labeled

What is Normal?

- Triangular shape

- Thin walled

- Smaller than the LV: A general rule of thumb is that the RV should be ~2/3 the size of the LV [19].

- The RV should squeeze inwards uniformly, with the free wall moving toward the septum during systole.

Figure 18: Subxiphoid 4 chamber view demonstrating normal RV size and function

What is NOT Normal

- Visually, if the RV is equal to or larger than the LV, then there is likely RV dilation.

- Visually reduced contraction.

- Decreased or akinetic RV free wall motion (Mcconnell’s Sign)

Figure 19: Subxiphoid 4 chamber view demonstrating dilated RV with reduced function

Apical Four Chamber

Apical 4 Chamber (A4C)

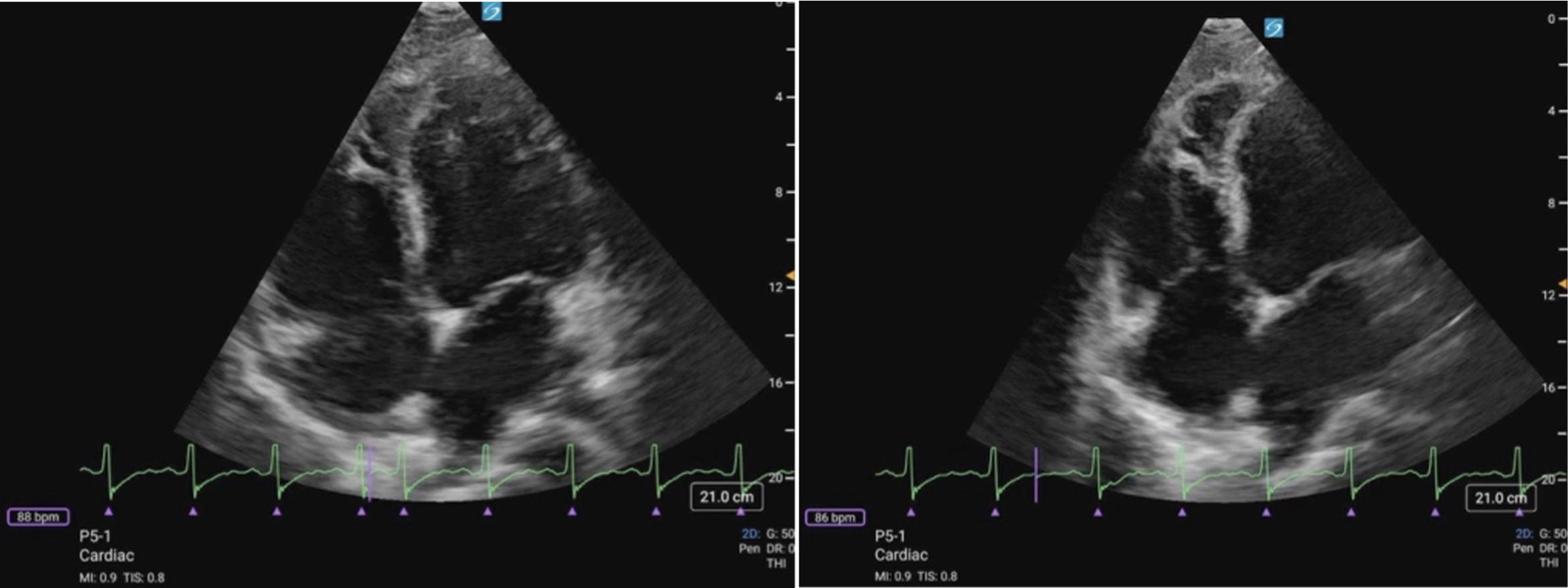

In the A4C view, the RV can be assessed in terms of size, free wall motion, and comparison to the LV. It is the preferred view to assess RV size in comparison to the LV. This view also allows visualization of the RV free wall from base to apex and provides a qualitative impression of RV function.

Of note, the RV contracts predominantly through longitudinal shortening, with the base of the free wall moving toward the apex, accompanied by a helical twist at the outlet. This is in contrast with the LV, which relies more on circumferential contraction and radial thickening, with a more pronounced twist between the entire base and apex [18].

Figure 11 (a) A4C Cardiology convention LV focused compared to (b) RV focused. Note how in the RV focused view, the LV may be out of frame, but the RV free wall and apex are fully visualized.

Figure 11 (a) A4C Cardiology convention LV focused compared to (b) RV focused. Note how in the RV focused view, the LV may be out of frame, but the RV free wall and apex are fully visualized.

What is Normal?

- Triangular shape

- Thin walled

- Smaller than the LV: A general rule of thumb is that the RV should be ~2/3 the size of the LV [19].

- The RV should squeeze inwards uniformly, with the free wall moving toward the apex during systole (figure 12).

Figure 12. A4C Cardiology convention demonstrating normal RV function. Note the movement of the RV free wall as it primarily moves toward the apex during systole, while also contracting inward toward the IVS.

What is NOT Normal?

- Visually, if the RV is equal to or larger than the LV, then there is likely RV dilation. In severely dilated RVs, the LV will appear to look compressed by the RV.

- RV apical dominance: the apex will become dominated by RV rather than the LV (figure 13).

- Septal shifting: the IVS may be observed shifting towards the LV or appear to “bounce” during the cardiac cycle when RV pressures are elevated (figure 14).

- Visually reduced contraction (figure 15).

- Decreased or akinetic RV free wall motion: The RV free wall is moving less effectively toward the apex during systole.

> Mcconnell’s Sign (figure 16): Acute regional dysfunction where the basal/mid-RV free wall motion is decreased or akinetic, while the RV apex continues to contract normally. It is classically described in acute pulmonary embolism in adults. In children, this pattern can be seen in acute RV strain states, but it is not specific. Mcconnell’s sign can help distinguish sudden afterload stress from chronic conditions where the entire RV, including the apex, is affected (figure 15).

Figure 13: Cardiology convention A4C view demonstrating marked RV dilation and RV apical dominance

Figure 14: A4C cardiology convention demonstrating RV dilation and septal shifting. Video Courtesy of David Kirschner, used with permission

Figure 15. A4C cardiology convention demonstrating reduced RV function with reduced RV free wall function

Figure 16. A4C cardiology convention demonstrating Mcconnell’s sign. Note how the RV apex is contracting well, while there is reduced function of the basal/mid RV free wall. Video courtesy of Dr. Kelly Maurelus & Matthew Riscinti, Kings County Emergency Medicine , via POCUS Atlas. Used under CC BY-NC 4.0 license.

Fractional Area Change (FAC) & Tricuspid annular plane systolic excursion (TAPSE):

FAC and TAPSE are quantitative measures of RV systolic function that can provide indirect information about RV performance; however, these represent advanced PoCUS skills and will be covered in a future KidSONO advanced practice module.

Parasternal Short Axis

Parasternal Short Axis (PSAX/PSSA)

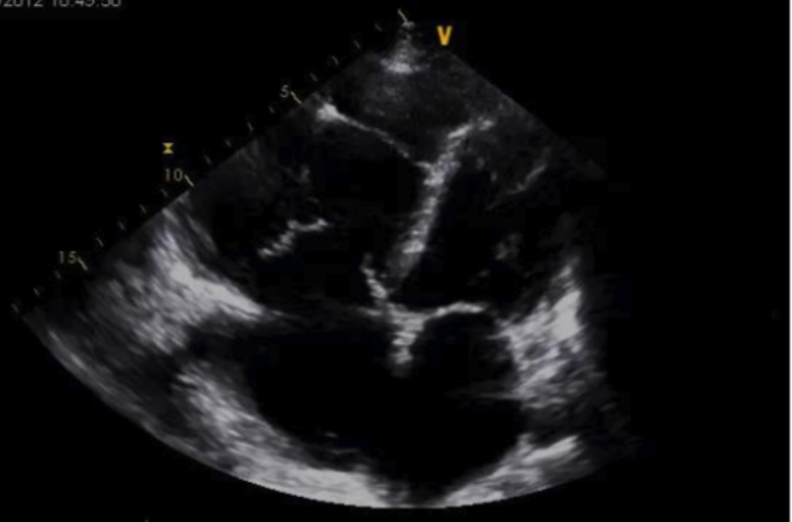

The PSAX view provides a cross-sectional image of the ventricles, allowing simultaneous visualization of the RV and LV. For RV strain assessment, this view is useful for evaluating RV size, function. It is also the preferred view to assess the shape and position of the IVS.

The RV appears as a crescent-shaped structure anteriorly, wrapping around the circular LV cavity, with the septum forming a smooth, curved border between the two chambers (figure 8).

What is Normal?

- Crescent shaped

- Smaller than the LV

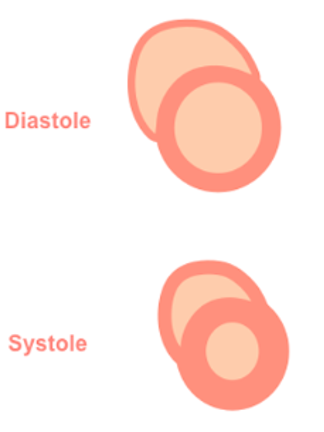

- In a normal PSAX view, the septum maintains a round, inward curvature toward the RV throughout the cardiac cycle.

Figure 7: Illustration of normal septal shape during systole and diastole in the PSAX view

Figure 8: PSAX view. Note how the septum maintains its round inward curvature during throughout the entire cardiac cycle and the crescent shape of the RV in the near field.

What is NOT Normal?

- Visually, if the RV is equal to or larger than the LV, then there is likely RV dilation. In severely dilated RVs, the LV will appear to look compressed by the RV

- Visually reduced contraction

- Septal flattening or becoming D-shaped when RV pressure > LV pressure

Septal Flattening

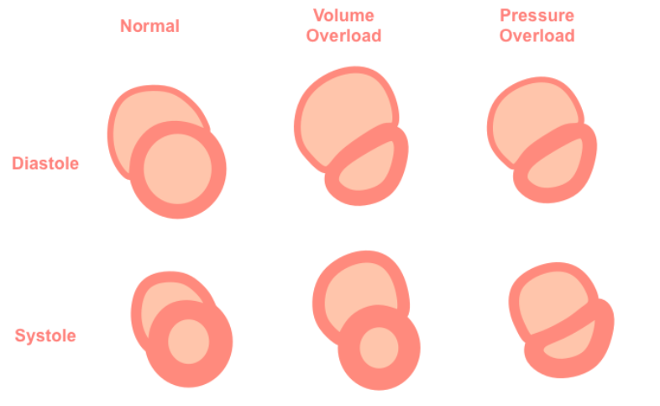

In the PSAX view, the LV will appear as a “D-shaped” structure. This is the result of RV volume overload (RVVO) or RV pressure overload (RVPO).

· In RVVO the septum is flattened only during diastole. This is the result of elevated RV volume filling at the expense of the LV, and causes the LV shape to deform by the end of diastole

· In RVPO the septum will be flattened throughout the entire cardiac cycle.

It is important to remember that to accurately assess septal position, the PSAX view should be obtained at the level of the papillary muscles, rather than at the mitral valve. At the mitral valve level, surrounding structures may artificially preserve septal shape despite significant RV loading.

It is also important to note that intra-cardiac shunts (e.g., VSDs) and arrhythmias can also limit the reliability of RV/LV and septal assessments in the PSAX view.

Figure 9: Illustration of Septal flattening or “D-sign” as seen in the PSAX view

Figure 10: PSAX view “D-sign” throughout cardiac cycle indicative of RVVO/RVPO