As with all pediatric cardiac PoCUS, obtaining adequate imaging windows remains a central challenge in the assessment of RV strain. Visualizing the RV can be additionally challenging due to anatomical considerations such as cross-sectional variability and the more horizontal cardiac axis often seen in infants and young children [10]. Lung interference is also common, as right heart structures are frequently obscured by overlying lung tissue. In addition, child cooperation is a recurring obstacle in pediatric imaging; the use of caregivers and distraction techniques is often necessary to improve success.

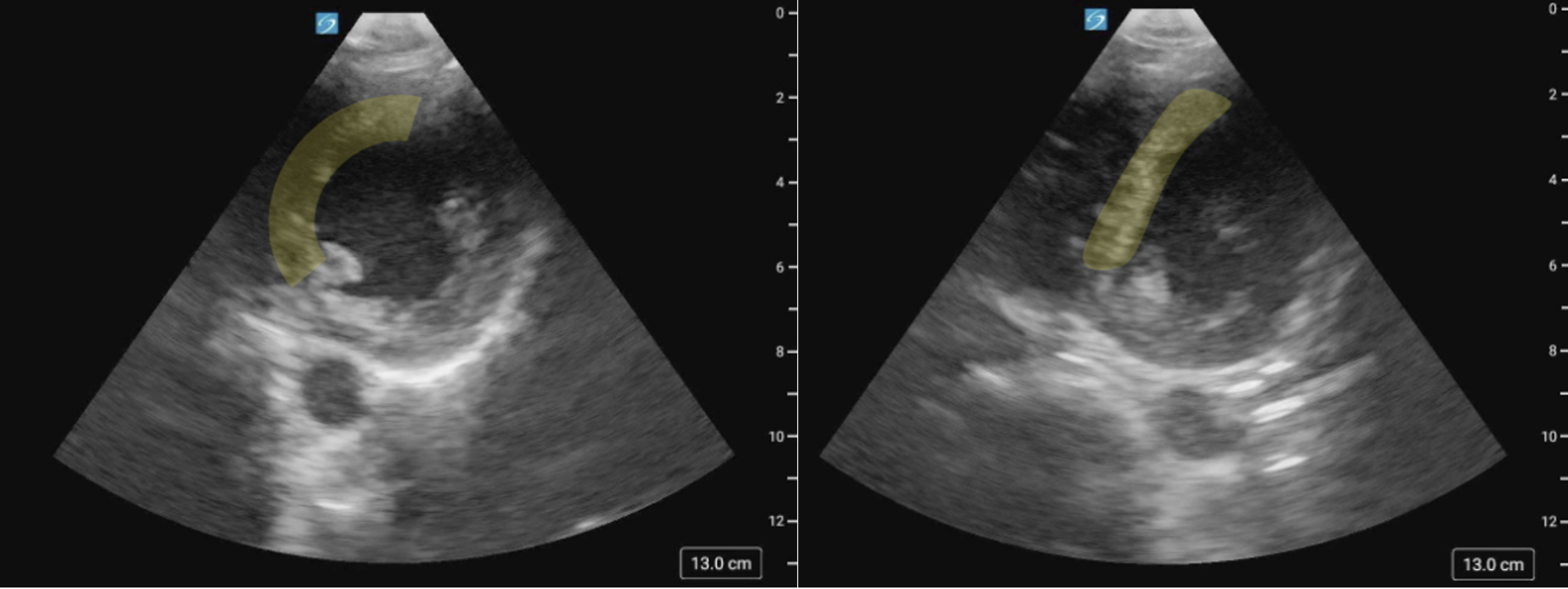

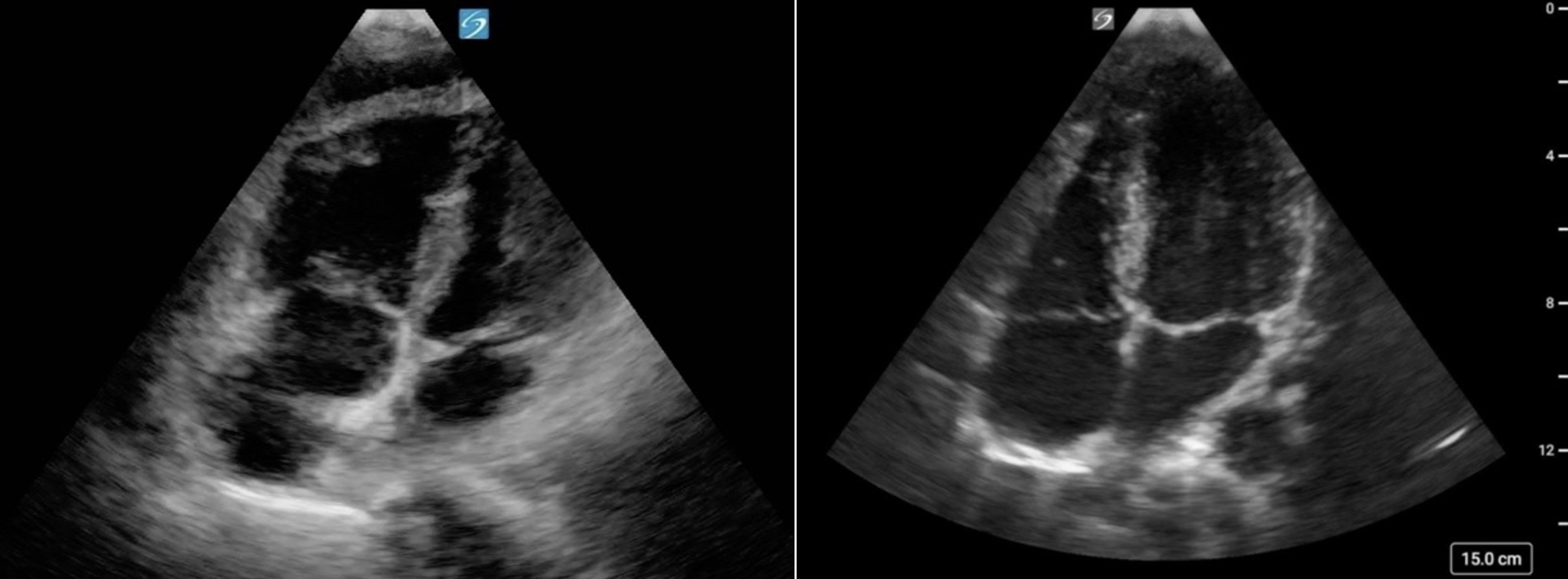

Similar to LV function assessment, RV strain imaging is susceptible to foreshortening and off-axis imaging. In the PSAX window, a low imaging window or off-axis rotation can produce apparent septal flattening (“pseudoflattening”) (figure 24, 25), which may mimic RVVO and/or RVPO and lead to inappropriate conclusions or interventions [17, 24,25]. In the A4C view, foreshortening may occur when imaging from too high of an intercostal space, making the RV appear truncated or blunted (figure 26,27). Always confirm you are at the appropriate intercostal space by scanning through adjacent levels in each window.

Similarly, IVC interpretation carries technical limitations. In children receiving positive pressure ventilation, the IVC shows reversed respiratory variation, and its craniocaudal and mediolateral motion during respiration can introduce apparent changes in caliber, potentially leading to overestimation of collapsibility or distensibility [22,23]. In addition, only the extremes (marked collapse or minimal/no collapse) are truly informative in pediatric 2D IVC assessment; intermediate appearances are unreliable and should be interpreted cautiously within the overall clinical context [21].

Because of these technical challenges, some studies have shown that in pediatric RV strain PoCUS examinations, fewer than half of the obtained images are adequate for qualitative assessment [10]. Even in light of these limitations, supplemental qualitative measures are still not recommended for pediatric RV strain PoCUS at this time due to the difficulty in defining normal values for pediatric populations [26]. Quantitative assessment should be saved for formal echocardiography, where time permits access to normal values charts relative to age and body surface area.

In practice, qualitative interpretation often relies on comparing RV size and function to that of the LV. However, this relative approach carries pitfalls: if the LV is dilated or dysfunctional, the RV may appear deceptively normal by comparison, when it may also be abnormal (figure 28). It is therefore important to always consider global cardiac function when interpreting RV findings.

Lastly, differentiation of RVVO and RVPO septal flattening can be difficult, particularly in PoCUS settings without ECG gating. Any flattening of the IVS should prompt formal echocardiography for further evaluation [17]. Formal echocardiography should also be pursued when image quality is suboptimal, interpretation is uncertain, or there are clinical concerns for RV strain, even if PoCUS findings appear normal [17].

Figure 24 (a) PSAX image of the IVS on axis versus (b) Pseudoflattening of the IVS in the same patient, secondary to a low scanning window.

Figure 25 (a) PSAX view of the IVS on axis versus (b) Pseudoflattening of the IVS in the same patient, secondary to a low scanning window.

Figure 26. Foreshortened RV in the A4C view

Figure 27. (a) Foreshortened RV in the A4C view. Note the blunted RV apex and loss of the triangular apical tip compared to (b) Elongated RV with triangular tip in the A4C view

Figure 28: A4C cardiology convention, showing RV dilation alongside LV dilation. Although the RV appears smaller than the LV, it is also enlarged.