Ocular complaints are a common reason for presentation to the pediatric emergency department (ED). According to a five-year retrospective study in Ontario, children accounted for approximately 19% of the 774,057 eye-related ED visits, underscoring the substantial pediatric burden of ocular emergencies [1]. While many cases are benign, some may reflect serious ocular trauma or underlying systemic or neurological disease, making timely recognition and referral essential for preserving vision and preventing complications [2].

Ocular complaints, particularly in children, represent a diagnostic challenge to many non-ophthalmology specialists. Traditional diagnostic methods, such as direct fundoscopic examination performed by non-experts, can be challenging given the limited cooperation of the younger pediatric patients and the challenging and technical nature of the exam. Other modalities such as computed tomography (CT), or magnetic resonance imaging (MRI), can be time-consuming, expose children to radiation, may require transportation and sedation, and may not always be readily available. Finally, in many emergency settings, timely ophthalmology consultation may also be limited, further complicating or delaying the evaluation of pediatric patients presenting with acute visual or ocular complaints.

In recent years, point-of-care ultrasound (PoCUS) has emerged as a valuable tool for evaluating ocular complaints in the pediatric ED. It allows for rapid, bedside imaging performed by emergency physicians, providing real-time diagnostic information without the typical challenges associated with fundoscopic exam [3]. As PoCUS becomes increasingly integrated into pediatric emergency care, there is a growing body of evidence supporting its clinical utility in detecting ocular abnormalities [3-6]. Given the frequency of ocular complaints in children and the need for a more user-friendly diagnostic tool, PoCUS offers a compelling adjunct to fundoscopy and other imaging (CT/MRI) in appropriate clinical contexts.

This module focuses on the normal and abnormal anatomy of the pediatric eye, providing learners with the foundational skills to identify common anterior and posterior segment findings using PoCUS. Assessment of the optic nerve for raised intracranial pressure or papilledema is beyond the scope of this module and is addressed in detail in a separate KidSONO module.

Why Ultrasound?

Traditionally, bedside emergency evaluation of ocular pathology has relied on physical examination and direct fundoscopy. Direct fundoscopy is the primary examination for visualizing posterior segment pathology, including retinal detachment, vitreous detachment, vitreous hemorrhage, and intraocular masses, with MRI occasionally used for deeper structural or space-occupying lesions. However, fundoscopy presents significant challenges, particularly in children and when performed by non-ophthalmologists. It can be technically difficult to carry out, and many non-ophthalmology physicians report a lack of confidence in performing and accurately interpreting the exam [7-10]. Children’s cooperation can be particularly limited due to young age, developmental stage, anxiety, or fear, all of which may compromise the reliability of fundoscopic findings [3]. Moreover, the technique is known to have high false-negative rates when performed by non-ophthalmologists, emphasizing the importance of examiner expertise [9]. Assessment of anterior segment pathology such as intraocular foreign bodies, corneal injuries, or lens abnormalities, typically relies on slit-lamp examination or CT imaging. Slit lamp assessment is a challenging skill at the bedside due to equipment limitations, lack of consistent training, routine use, and patient compliance. CT carries the disadvantage of ionizing radiation exposure, which is particularly concerning in pediatric populations.

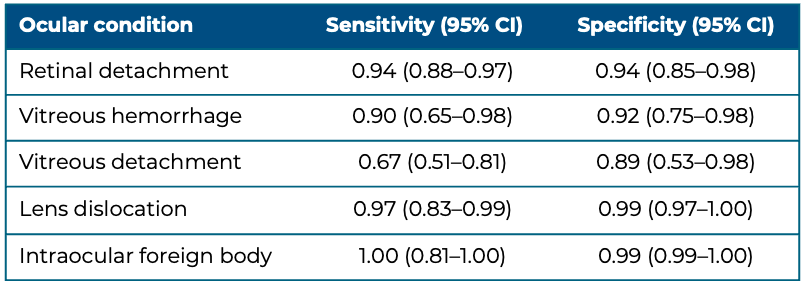

PoCUS offers a valuable alternative or precursor to these conventional methods, allowing real-time visualization of both anterior and posterior ocular structures at the bedside. Its versatility, portability, cost-effectiveness, and safety have contributed to its growing role as a frontline imaging modality in pediatric care. When performed by trained emergency physicians, PoCUS has demonstrated high sensitivity and specificity for a range of ocular pathologies. In a systematic review and meta-analysis in adult populations, PoCUS achieved high sensitivity and specificity across multiple ocular conditions (Table 1) [11].

Table 1. Diagnostic accuracy of PoCUS [11].

Ocular PoCUS, like other PoCUS applications, is a skill that can be readily acquired through focused training combining didactic instruction and hands-on practice [12, 13]. It has been demonstrated that PEM physicians are able to rapidly achieve competency in ocular scanning, even for more advanced applications such as optic nerve assessment (covered in a separate KidSONO module), highlighting the overall ease and accessibility of ocular PoCUS training [14].

Given these advantages, the use of PoCUS for ocular complaints is endorsed by several professional societies [15, 16]. While ocular PoCUS is not intended to replace fundoscopy or advanced imaging such as CT or MRI, it functions as an effective adjunctive tool to support rapid bedside diagnosis and facilitate timely ophthalmology consultation when abnormalities are detected. In practice, ocular PoCUS should be applied as a “rule-in” test, helping confirm suspected pathology and prioritize urgent referral, rather than a “rule-out” test in cases where the clinical history or presentation raises concern for serious ocular disease.