Apical 4 Chamber (A4C)

In the A4C view, the RV can be assessed in terms of size, free wall motion, and comparison to the LV. It is the preferred view to assess RV size in comparison to the LV. This view also allows visualization of the RV free wall from base to apex and provides a qualitative impression of RV function.

Of note, the RV contracts predominantly through longitudinal shortening, with the base of the free wall moving toward the apex, accompanied by a helical twist at the outlet. This is in contrast with the LV, which relies more on circumferential contraction and radial thickening, with a more pronounced twist between the entire base and apex [18].

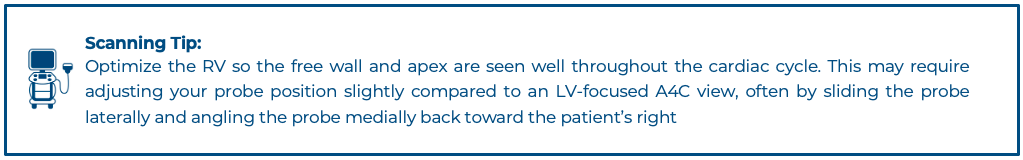

Figure 11 (a) A4C Cardiology convention LV focused compared to (b) RV focused. Note how in the RV focused view, the LV may be out of frame, but the RV free wall and apex are fully visualized.

What is Normal?

- Triangular shape

- Thin walled

- Smaller than the LV: A general rule of thumb is that the RV should be ~2/3 the size of the LV [19].

- The RV should squeeze inwards uniformly, with the free wall moving toward the apex during systole (figure 12).

Figure 12. A4C Cardiology convention demonstrating normal RV function. Note the movement of the RV free wall as it primarily moves toward the apex during systole, while also contracting inward toward the IVS.

What is NOT Normal?

- Visually, if the RV is equal to or larger than the LV, then there is likely RV dilation. In severely dilated RVs, the LV will appear to look compressed by the RV.

- RV apical dominance: the apex will become dominated by RV rather than the LV (figure 13).

- Septal shifting: the IVS may be observed shifting towards the LV or appear to “bounce” during the cardiac cycle when RV pressures are elevated (figure 14).

- Visually reduced contraction (figure 15).

- Decreased or akinetic RV free wall motion: The RV free wall is moving less effectively toward the apex during systole.

> Mcconnell’s Sign (figure 16): Acute regional dysfunction where the basal/mid-RV free wall motion is decreased or akinetic, while the RV apex continues to contract normally. It is classically described in acute pulmonary embolism in adults. In children, this pattern can be seen in acute RV strain states, but it is not specific. Mcconnell’s sign can help distinguish sudden afterload stress from chronic conditions where the entire RV, including the apex, is affected (figure 15).

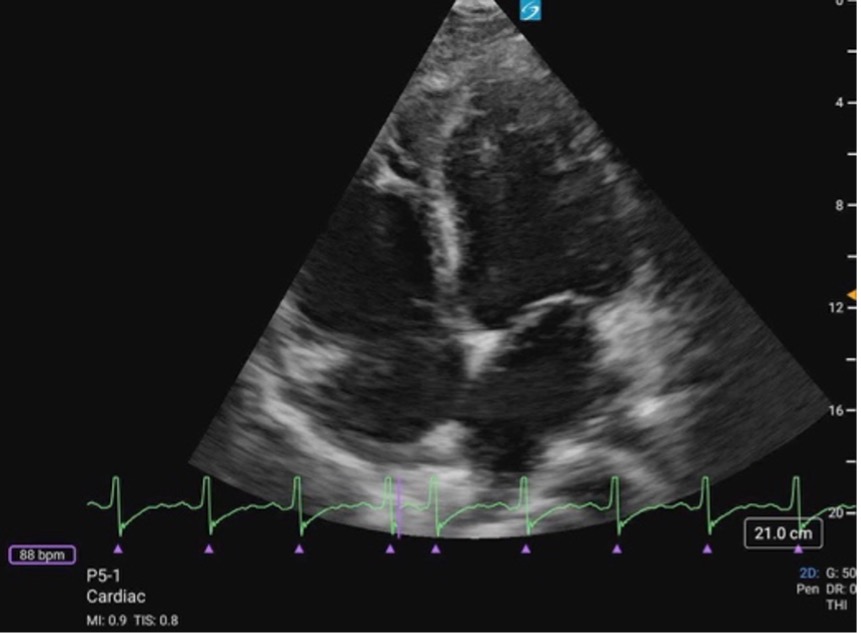

Figure 13: Cardiology convention A4C view demonstrating marked RV dilation and RV apical dominance

Figure 13: Cardiology convention A4C view demonstrating marked RV dilation and RV apical dominance

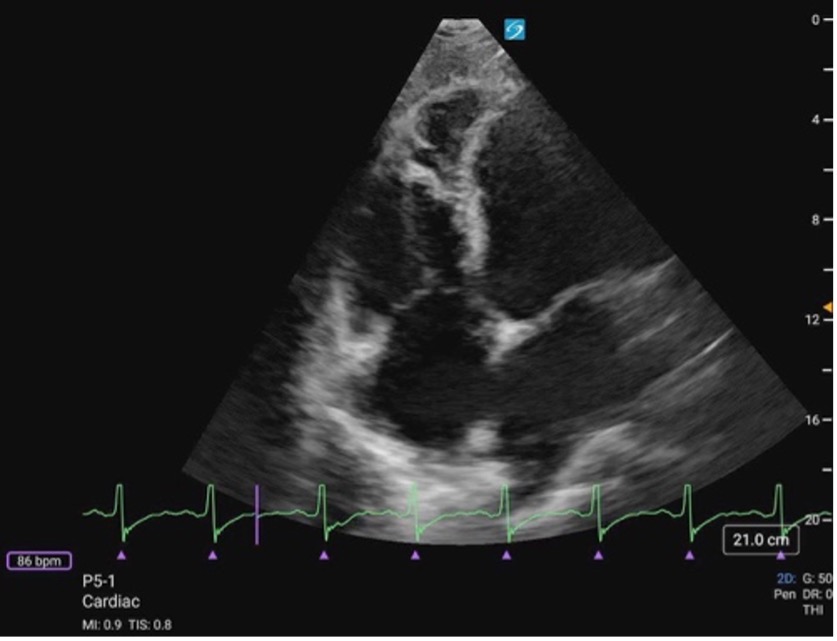

Figure 14: A4C cardiology convention demonstrating RV dilation and septal shifting. Video Courtesy of David Kirschner, used with permission

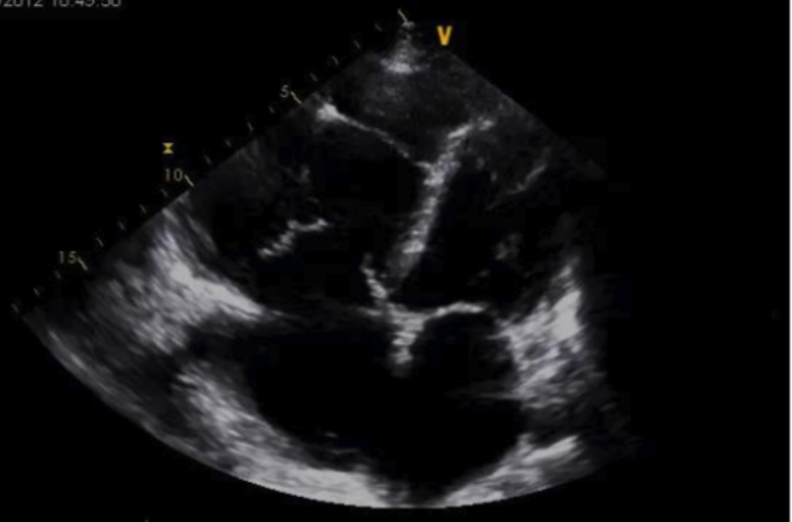

Figure 15. A4C cardiology convention demonstrating reduced RV function with reduced RV free wall function

Figure 16. A4C cardiology convention demonstrating Mcconnell’s sign. Note how the RV apex is contracting well, while there is reduced function of the basal/mid RV free wall. Video courtesy of Dr. Kelly Maurelus & Matthew Riscinti, Kings County Emergency Medicine , via POCUS Atlas. Used under CC BY-NC 4.0 license.

Fractional Area Change (FAC) & Tricuspid annular plane systolic excursion (TAPSE):

FAC and TAPSE are quantitative measures of RV systolic function that can provide indirect information about RV performance; however, these represent advanced PoCUS skills and will be covered in a future KidSONO advanced practice module.